FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | March 23, 2015

Sewage — yes, poop — could be a source of valuable metals and critical elements

Note to journalists: Please report that this research will be presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

A press conference on this topic will be held Tuesday, March 24, at 10:30 a.m. Mountain time in the Colorado Convention Center. Reporters may check-in at Room 104 in person, or watch live on YouTube http://bit.ly/ACSLiveDenver. To ask questions, sign in with a Google account.

DENVER, March 23, 2015 — Poop could be a goldmine — literally. Surprisingly, treated solid waste contains gold, silver and other metals, as well as rare elements such as palladium and vanadium that are used in electronics and alloys. Now researchers are looking at identifying the metals that are getting flushed and how they can be recovered. This could decrease the need for mining and reduce the unwanted release of metals into the environment.

A talk about their recent work will be one of nearly 11,000 presentations here at the 249th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS), the world’s largest scientific society, taking place here through Thursday.

“If you can get rid of some of the nuisance metals that currently limit how much of these biosolids we can use on fields and forests, and at the same time recover valuable metals and other elements, that’s a win-win,” says Kathleen Smith, Ph.D.

“There are metals everywhere,” Smith says, noting they are “in your hair care products, detergents, even nanoparticles that are put in socks to prevent bad odors.” Whatever their origin, the wastes containing these metals all end up being funneled through wastewater treatment plants, where she says many metals end up in the leftover solid waste.

At treatment plants, wastewater goes through a series of physical, biological and chemical processes. The end products are treated water and biosolids. Smith, who is at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), says more than 7 million tons of biosolids come out of U.S. wastewater facilities each year. About half of that is used as fertilizer on fields and in forests, while the other half is incinerated or sent to landfills.

Smith and her team are on a mission to find out exactly what is in our waste. “We have a two-pronged approach,” she says. “In one part of the study, we are looking at removing some regulated metals from the biosolids that limit their use for land application.

“In the other part of the project, we’re interested in collecting valuable metals that could be sold, including some of the more technologically important metals, such as vanadium and copper that are in cell phones, computers and alloys,” Smith said. To do this, they are taking a page from the industrial mining operations’ method book and are experimenting with some of the same chemicals, called leachates, which this industry uses to pull metals out of rock. While some of these leachates have a bad reputation for damaging ecosystems when they leak or spill into the environment, Smith says that in a controlled setting, they could safely be used to recover metals in treated solid waste.

So far, her group has collected samples from small towns in the Rocky Mountains, rural communities and big cities. For a more comprehensive picture, they plan to combine their information with many years’ worth of existing data collected by the Environmental Protection Agency and other groups at the USGS.

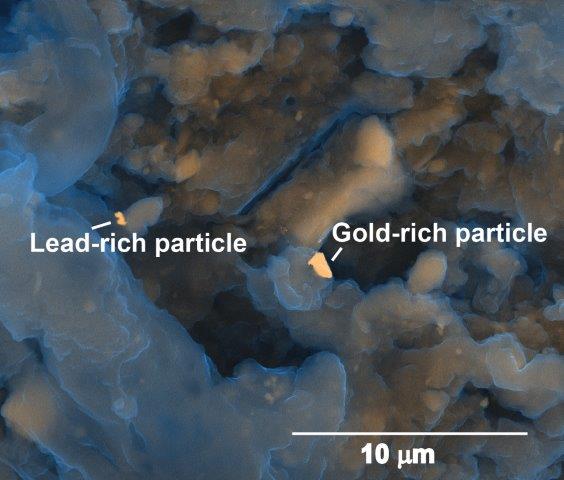

In the treated waste, Smith’s group has already started to discover metals like platinum, silver and gold. She states that they have observed microscopic-sized metal particles in biosolids using a scanning electron microscope. “The gold we found was at the level of a minimal mineral deposit,” she says, meaning that if that amount were in rock, it might be commercially viable to mine it. Smith adds that “the economic and technical feasibility of metal recovery from biosolids needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.”

In a recent Environmental Science & Technology paper (2015, DOI: 10.1021/es505329q), another research group also studying this issue calculated that the waste from 1 million Americans could contain as much as $13 million worth of metals. That’s money that could help fuel local economies.

The researchers acknowledge funding from the U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Resources Program.

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. With more than 158,000 members, ACS is the world’s largest scientific society and a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences. Its main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Media Contact

303-228-8406 (Denver Press Center, March 21-25)

Michael Bernstein

202-872-6042 (D.C. Office)

301-275-3221 (Cell)

m_bernstein@acs.org

Katie Cottingham, Ph.D.

301-775-8455 (Cell)

k_cottingham@acs.org

High-resolution image