Chemical Hearth

Dedicated at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville on March 1, 2024

On October 27, 1895, a fire erupted in the Rotunda, in the heart of the University of Virginia (UVA) campus.

The Rotunda — designed by Thomas Jefferson, the university’s founder and a former U.S. President — was one of the original campus buildings, completed in 1828. Faulty wiring set it ablaze. While students and faculty rushed to save books and art, much of the interior was destroyed. But an important, hidden part of the Rotunda survived. Its existence remained secret until many years after the conflagration.

The Rotunda’s surviving artifact is a workspace with an integrated fireplace, known as a chemical hearth, which was designed by John Patten Emmet, M.D. (1796-1842), the university’s professor of natural history. In the 1820s, enslaved Black Americans and others built the hearth in an alcove in the building’s lower east oval room, along with all the architecture required for high-temperature experiments. The hearth had several workstations that operated with fully functional furnaces. Flues and vents pulled fresh air into the fires and drew smoke and fumes out.

Students used the room to conduct wood- and coal-powered experiments, observing through their own actions how substances react when heated. Emmet believed chemistry students needed this type of hands-on instruction, which was unusual for the era.

In fact, the hearth embodies a crucial phase in the evolution of chemistry education. In the 19th century, most laboratories were located in private homes and used by the residents. But labs were also gradually being introduced in universities as learning spaces for young adults.

While a few other hearths existed in medical and chemical classrooms around the world, experts suspect UVA’s intact hearth is the oldest remaining hands-on site for teaching chemistry in the U.S.

About 15 years after it was built, UVA’s hearth fell into disuse, and the university sealed it off behind a wall.

As time passed, the memory of its presence faded, until preparations for a Rotunda restoration unearthed it in 2013. Now, an estimated 200,000 visitors see the restored hearth every year during the university’s campus tours.

Contents

How to Find the University of Virginia Rotunda

The University of Virginia offers historic tours of the campus, including the Rotunda and its chemical hearth, which is on the building’s ground floor. The Rotunda is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Website: rotunda.virginia.edu

Address: 1826 University Ave., Charlottesville, VA 22903

History of chemistry education

The average person living in the 18th century used fireplace ashes to make lye and soap, prepared dyes from plants and seeds, and preserved food with salt. Whether they realized it or not, they were doing chemistry. But at the time in the U.S., only medical doctors received a formal chemistry education as part of their training.

Benjamin Franklin helped establish the first undergraduate chemistry course at the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania) in the 1750s. The college’s provost at the time, William Smith, taught a course titled “Chemistry, Fossils, and Agriculture,” and the college became the first in the colonies to teach science as a regular part of the general curriculum.

Chemistry education continued to evolve in the 1770s when two future U.S. presidents prioritized the subject at the College of William and Mary: James Madison taught chemistry in a natural philosophy course, and Jefferson established a professorship for “Chymistry and Medicine.”

Around the same time, Benjamin Rush took over the chemistry professorship in Philadelphia. Rush had studied medicine and chemistry at the University of Edinburgh and now drew on those lessons to write the first chemistry textbook published in the U.S: "Syllabus of a Course of Lectures on Chemistry." Rush is often credited as the country’s founder of chemistry education. He taught hundreds of medical students and gave many public lectures.

Rush’s guiding principle was that chemistry “teaches the effects of heat and mixture.” And he demonstrated chemical reactions, such as sulfuric acid and iron combining to produce hydrogen gas. But hands-on experiments for students were rare, since lab apparatus was expensive and often had to be imported from Europe. So students would only watch demonstrations, rather than carry out the procedures themselves.

That began to change in the early 19th century. At the University of Giessen, in Germany, chemist Justus Liebig assigned students laboratory spaces and individual experiments.

Meanwhile in U.S. medical labs, academics sought to popularize chemical experimentation. The influence of this pedagogy diffused throughout institutions in the U.S., and as Jefferson carried out design plans for the nascent University of Virginia, which he founded in 1819, laboratory chemistry found a permanent home — in a hearth.

Early chemistry courses did not much resemble a modern course in chemistry.

The content was meager and the teaching methods were superficial and rudimentary... In the early academies and colleges, chemistry was taught entirely by textbook and lectures, with the gradual introduction of demonstration experiments. The scarcity of suitable apparatus dictated that demonstrations be performed only by the teacher; students had no opportunity to do individual work in a laboratory.“

— George H. Fisher, The Science Teacher, April 1986

Chemistry in the Rotunda

Jefferson developed UVA with a special attention to science education. He owned dozens of chemistry books, including titles that illustrated modern laboratory constructions. According to historical records, he and Emmet exchanged ideas about the kinds of scientific spaces the Rotunda should contain.

Emmet was educated at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. He also set up a lab in his father’s home to study chemistry. For his medical degree, he prepared a dissertation on “The Chemistry of Animated Matter.” After moving to Charleston, S.C., he delivered public lectures on chemistry that attracted the attention of Jefferson, who subsequently invited him to become a natural history professor at UVA.

Emmet wanted the university to provide a large lab space, possibly even a separate building, for chemistry instruction. However, in 1824 officials had set aside only one basement room in the Rotunda as a chemistry lab. When Emmet arrived the following year to teach, he complained to Jefferson that the space was too small: “Even a small furnace” made the space “oppressively hot & myself even more so,” he noted.

A larger space would allow students to get hands-on experience and analyze minerals, reduce metals, and prepare medical formulations themselves. “Verbal instruction alone,” Emmet wrote, “is altogether inadequate.”

Emmet’s determination to provide hands-on instruction was rooted in experiences with other chemical hearths from that era, including lab space he worked in as a student at the College of Physicians and Surgeons. At the time, medical schools typically used chemical hearths for instruction and to prepare medicines in early anatomical theaters.

Jefferson initially resisted, but eventually approved an expanded space at UVA. Emmet was granted two large rooms: one to use for lectures, and one for laboratory experiments.

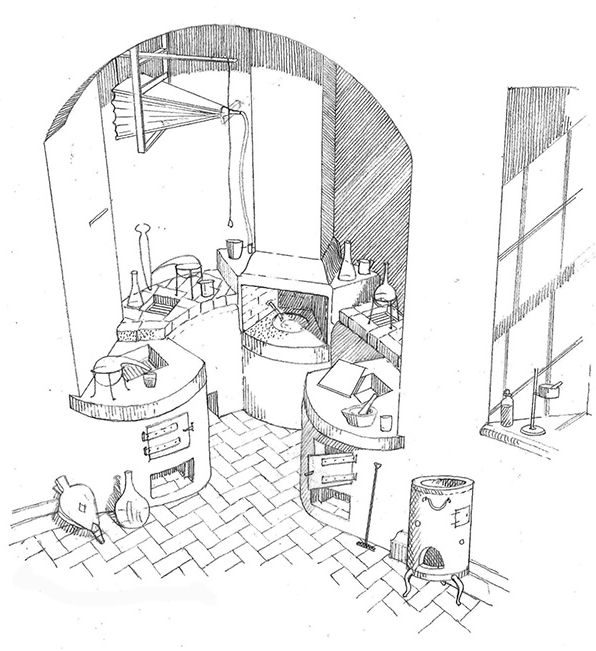

The space dedicated to chemical demonstrations featured multiple furnaces, ventilation, a brick-lined duct, a sand bath, and a water bath, and it evolved throughout Emmet’s two decades at UVA. University records indicate Emmet requested fireplace improvements, waterproof containers, and repairs to the hearth during his tenure. In addition to education, Emmet and his colleagues used the chemical hearth for their own research, analyzing the composition of gastric juices.

Professor Emmet believed that the students should do the experiments themselves, which was a change from the practice of the time of teaching by demonstration.”

— Brian Hogg, senior preservation planner in the Office of the Architect for the University, UVA Today, March 21, 2016

Disuse followed by rediscovery

In 1841-42, the university moved the laboratory into what had been the lecture room in the lower west oval room in the Rotunda. School officials believe that the alcove housing the chemical hearth was bricked up around that time, allowing it to survive the 1895 fire and to remain hidden during a 1970s renovation.

The hearth was rediscovered during renovations in 2013. An architect peered through a hole in a wall inside the Rotunda and noticed plaster, a painted wall, and an unusual piece of cut stone. Probes confirmed it was part of a larger feature of the building, and the area was examined in detail.

The chemical hearth measures approximately 6 feet wide and 5 feet deep, and it contains workstations made of brick, stone, and plaster. Architectural investigators with UVA evaluated the space as if it were a time capsule. Around the hearth, the team has found remnants of Emmet’s laboratory class experiments, such as crucibles, glass tubes, charcoal, and sheets of glass.

An architectural conservator with the university suggested in an interview that Emmet made some of his own equipment, based on remaining fragments of pipettes, clay crucibles, and melted glass found at the hearth. Emmet’s own records, preserved in the University’s Small Special Collections Library, include drawings of beakers, a copper boiler, scales, weights, and other devices.

Ripple effects

After student-centered labs, like the UVA hearth, changed chemistry education at a few progressive colleges, they began appearing at many other institutions. By the end of the 19th century, chemistry — including hands-on experiments — was a common subject available for students at universities as well as city high schools.

Thanks in part to this improvement in education, chemical theories pushed ahead rapidly. In the 19th century, advances such as Dalton’s atomic theory and the theory of chemical structure influenced scientists’ chemical understanding. In turn, that knowledge was spread through chemistry textbooks for children and young adults. The scope of basic chemistry education grew beyond early utilitarian reference points in agriculture and medicine as students could witness — and perform — chemical reactions explained by the burgeoning understanding of atoms and molecules.

This personal relationship with chemistry made up the core of Emmet’s philosophy as a teacher in the UVA Rotunda. “I have had in view what I consider of prime importance to the students of Chemistry, namely that they should operate for themselves,” he wrote. His chemical hearth helped realize those ambitions. And today, the intact hearth survives as an icon of the central importance of chemical education.

Landmark dedication and acknowledgments

Landmark dedication

The American Chemical Society (ACS) designated the University of Virginia Chemical Hearth as a National Historic Chemical Landmark (NHCL) in a ceremony at the campus in Charlottesville on March 1, 2024. The commemorative plaque reads:

The Rotunda of the University of Virginia contains the oldest remaining hands-on laboratory for teaching chemistry in the U.S. In the early 19th century, laboratories as learning spaces for students were beginning to be introduced, and hands-on experiments were rare. Natural history professor John Patten Emmet, M.D., championed this type of instruction at the university beginning in 1825. A workspace based on his design, where students could conduct experiments at high temperatures, was built in the Rotunda. It included a chemical hearth — an integrated fireplace that burned wood or charcoal. The university moved the laboratory to another location in 1841-42, and the chemical hearth was bricked up and forgotten until its rediscovery during renovations in 2013.

Acknowledgments

Written by Max Levy.

The author wishes to thank contributors to and reviewers of this booklet, all of whom helped improve its content, especially members of the ACS NHCL Subcommittee.

The nomination for this Landmark designation was prepared by the Virginia Section of the ACS.