It is early September. The power of chemistry to give life and the power of chemistry to kill are both on display here in mid-Michigan. The corn now stands well more than head-high. The tassels are past peak, just beginning to look a little tattered. Fields, orchards, and forests look robust this year. Most corn fields are beautiful, dark green, highlighted by the yellows of tassels and silk.

While most of the corn in the fields looks great, there are exceptions. Sections in some fields recall the best efforts of Oliver Wendell Douglas, short, stunted, and yellow. The importance to life of industrial chemistry is obvious. The yellow, stunted corn is nitrogen deficient. Applied nitrogen fertilizer is missing in those soils due to poor application or standing water. Corn needs nitrogen to support its amazing growth, nitrogen from ammonia produced by the chemical industry. Without it, poorly developed, stunted growth.

We, humans, require nitrogen too. We are made of proteins, proteins containing nitrogen. Half or more of the nitrogen in those proteins come from the industrial production of ammonia. The human population is approximately double what it would be without industrial production of ammonia. Half the planet’s population exists only because of industrial chemistry supplying the ammonia crops use and we eat.

Chemistry is responsible for life, at least the life of currently living humans. Chemistry also kills.

Death is on display here in mid-Michigan. Woody brush along roadways dies horribly this time of year. It twists and rapidly browns. The rapid mid-summer death concerned and saddened me. I was slow to realize what was going one when I first moved here. I learned it was intentional.

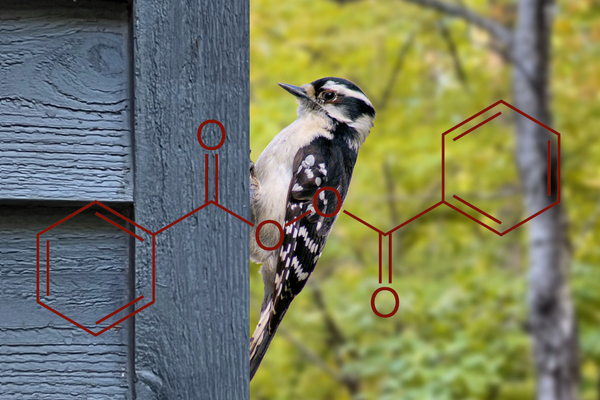

County road commissions in Michigan spray brush near roads with herbicides, most commonly triclopyr. Farmers frequently spray brush on fence lines at the edge of fields. Ditches are sprayed to control cattails and invasive phragmites, a tall wetland reed. Herbicides like glyphosate and imazapyr, with lower toxicity to aquatic species are used. These applications happen on the road edge, making the rapid browning of leaves visible. Vegetation dies where you can see it and the results are persistent. Dead vegetation frequently holds its leaves, grim reminders of life snuffed out.

Michigan tax dollars get spent on other programs that rely on pesticides. The herbicides used for brush control make the killing visible. The results from other applications are less visible. Mosquito control relies on biological treatment of standing water and fogging with non-selective pesticides. I see and hear the fogging, but I don’t see the dead mosquitos. I don’t see the beneficial insects killed either. I see herbicide use, and the lingering results of it.

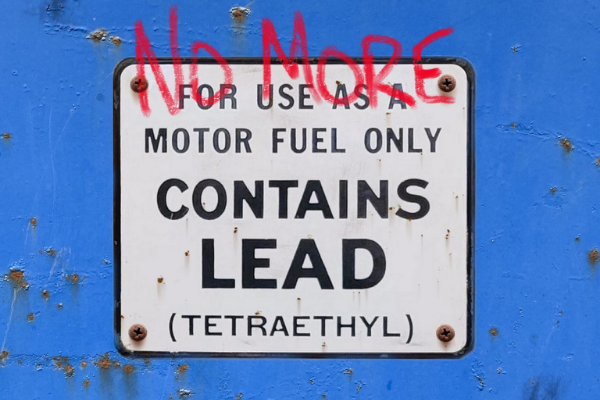

The chemical industry frequently takes it on the chin as many rile against chemical use. People complain of toxic chemicals. I don’t have much use for toxic as an adjective. Capable of causing harm to people or the planet actually seems to exclude very little. Herbicides are clearly toxic, a use of the word that feels accurate. Herbicides are compounds designed and produced to kill things. Some used in the past were pretty indiscriminate, not good for either plants or animals. Some still in use are acutely harmful to humans, in addition to killing plants.

Few biological alternatives to herbicides exist and none with the performance of synthetics. Mechanical removal is frequently the next best option, energy and labor intensive. Herbicides place us in a sustainability paradox. Spraying wide swaths of the world with the right toxic chemicals may be better than carbon-intensive, soil damaging alternatives. Herbicides continue to get better. More and more, compounds that interfere with metabolism using pathways unique to plants are used. These herbicides are safer for the environment since interactions with animals are unlikely. The pathways just aren’t there. There are still problems.

I was farming at the time glyphosate-based herbicides were coming on the market. Roundup seemed like it was heaven-sent. Compared with previously used materials like paraquat, it was way better. It was not acutely toxic, didn’t smell horrible, and lower dosing was required. It was said to degrade relatively quickly in the environment to benign materials. Glyphosate-based herbicides allowed wider use of no-till methods, reducing soil erosion and loss. Use only accelerated with the introduction of engineered resistance. Glyphosate became the most used agricultural chemical by far.

Bayer will stop selling their glyphosate-based Roundup herbicides for residential use starting in 2023. Bayer states glyphosate remains safe when used correctly. Growing evidence of health concerns are moving glyphosate toward professional application only, still far removed from the list of banned pesticides.

Herbicides, including glyphosate, will be with us for the foreseeable future. Toxic chemicals will continue to be sprayed into the environment on purpose. They’re simply too useful. Alternatives are too labor intensive, too costly. We can be certain of two things. First, chemists will continue to make better, safer alternatives. Second, the list of banned materials will continue to grow, in part because better alternatives will be developed, in part because unintended consequences will be recognized.

Mark Jones is a frequent speaker at a variety of industry events on industry related topics. He is a long-time supporter of ACS Industry Member Programs providing both written and webinar content, supporting the CTO Summits, and as a former member of Corporation Associates. He currently serves on the ACS Committee on Public Relations and Communications and the Chemical Heritage Landmark Committee. He is a member and former chair of the Chemical Sciences Roundtable, a standing roundtable of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Mark is the author of over a dozen U.S. patents and numerous publications.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the view of their employer or the American Chemical Society.

Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society (All Rights Reserved)