EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE | September 09, 2013

Artificial lung to remove carbon dioxide — from smokestacks

Note to journalists: Please report that this research was presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

A press conference on this topic will be held Monday, Sept. 9, at 3 p.m. in the ACS Press Center, Room 211, in the Indiana Convention Center. Reporters can attend in person or access live audio and video of the event and ask questions at www.ustream.tv/channel/acslive.

INDIANAPOLIS, Sept. 9, 2013 — The amazingly efficient lungs of birds and the swim bladders of fish have become the inspiration for a new filtering system to remove carbon dioxide from electric power station smokestacks before the main greenhouse gas can billow into the atmosphere and contribute to global climate change.

A report on the new technology, more efficient than some alternatives, is on the agenda today at the 246th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS), the world’s largest scientific society. The meeting, which features almost 7,000 presentations on new advances in science and other topics, continues here through Thursday in the Indiana Convention Center and downtown hotels.

With climate change now a major concern, many power plants rely on CO2 capture and sequestration methods to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Speaking at a symposium, “CO2 Separation and Capture,” Aaron P. Esser-Kahn, Ph.D., said he envisions new CO2-capture units with arrays of tubes made from porous membranes fitted side-by-side, much like blood vessels in a natural lung. Once fabricated to be highly efficient and scalable to various sizes by repeating units, these units can then be “plugged” into power plants and vehicles, not unlike catalytic converters, he explained.

To capture the most CO2, the Esser-Kahn group from the University of California, Irvine, first had to figure out the best pattern to pack two sets of different-sized tubes –– one for waste emissions and the other a CO2-absorbing liquid –– into the unit. “The goal is to cram as much surface area into the smallest space possible,” said Esser-Kahn.

They studied the way blood vessels are packed in the avian lung and the fish swim bladder. Birds need to exchange CO2 for oxygen rapidly, as they burn a lot of energy in flight, while fish need to control the amount of gas in their swim bladder effectively to move up and down in the water. “We’re trying to learn from nature,” said Esser-Kahn, adding that the avian lung and fish swim bladder are biologically well-suited systems for exchanging gases.

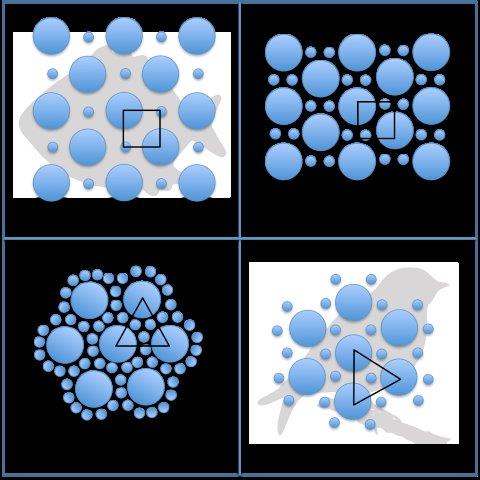

But the blood vessels in the avian lung and fish swim bladder are packed in different patterns. The avian lung consists of a hexagonal pattern where three large tubes form the vertices of a triangle and a small tube sits in the gap, while the fish swim bladder has a squarer pattern where a large and small tube alternate between vertices of a square. It turned out that this tube-packing challenge is a well-studied mathematical problem with nine unique solutions, or patterns, Esser-Kahn said.

The team used computer simulations to predict how efficient gas exchange would be for each pattern. Four were predicted to be highly efficient, including the avian lung’s hexagonal pattern and the fish swim bladder’s squarer pattern. However, the most efficient pattern was actually one not found in nature: the double-squarer pattern, similar to the squarer one in the fish swim bladder, but with two small tubes alternating with a large tube. Esser-Kahn’s team then synthesized miniature units up to a centimeter long and confirmed experimentally that the double-squarer pattern was the most efficient, outperforming the avian lung and fish swim bladder by almost 50 percent.

Now, scientists can conduct further research to improve CO2-capture units’ efficiencies by adjusting the sizes of the tubes, thicknesses of the tube walls and membrane materials that make up the tube walls. “Biological systems spent an incredible amount of time and effort moving towards optimization,” said Esser-Kahn. “What we have is the first step in a longer process.”

Other presentations at the symposium included:

- Novel carbon capture and sequestration: Biomimetic solid sorbents and gas shale analysis

- Process and thermodynamics considerations of CO2 capture from post-combustion flue gases

- Improving the regeneration of CO2-binding organic liquids with a polarity change

The authors acknowledge funding from the ACS Petroleum Research Fund, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and a 3M Non-Tenured Faculty Award.

To automatically receive news releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

# # #

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. With more than 163,000 members, ACS is the world's largest scientific society and a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences. Its main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Media Contact

During the national meeting, Sept. 6-11, the contacts can be reached at 317-262-5907.

Michael Bernstein

m_bernstein@acs.org

202-872-6042

Michael Woods

m_woods@acs.org

202-872-6293

High-resolution image