EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE | August 21, 2012

“CSI” technology holds potential in everyday medicine

Note to journalists: Please report that this research was presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

PHILADELPHIA, Aug. 21, 2012 — A scientific instrument featured on CSI and CSI: Miami for instant fingerprint analysis is forging another life in real-world medicine, helping during brain surgery and ensuring that cancer patients get effective doses of chemotherapy, a scientist said here today.

The report on technology already incorporated into instruments that miniaturize room-size lab instrumentation into devices the size of a shoebox was part of the 244th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society, the world’s largest scientific society. The meeting, which features about 8,600 reports with an anticipated attendance of 14,000 scientists and others continues here through Thursday.

Media Contact

During Aug. 17-23, the contacts can be reached at 215-418-2086.

Michael Bernstein

202-872-6042

m_bernstein@acs.org

Michael Woods

202-872-6293

m_woods@acs.org

“With both of the instruments we developed, no sample preparation is needed, which reduces analysis time from as much as several hours per sample to just a few seconds,” said Graham Cooks, Ph.D., who led the research team. “Rapid results are critical when a surgeon is operating on a brain tumor or when chemotherapy patients are being treated with powerful drugs that must be administered at precise levels.”

The instrument called a “desorption electrospray ionization” mass spectrometer, or DESI, was featured on both CSI and CSI: Miami as a tool to analyze fingerprints. However, this portable instrument can do so much more. It’s about the size of a shoebox and does not change or destroy the sample that is analyzed. Cooks’ students have even carried it into a grocery store and held it close to the outer surfaces of fruit and vegetables to detect pesticides and microorganisms. The team also used it to identify biomarkers for prostate cancer and to detect melamine, a potentially toxic substance that showed up in infant formulas in China in 2008 and in pet food in the U.S. in 2007. In addition, DESI can detect explosives on luggage.

Now, Cooks’ team at Purdue University is teaming up with collaborators led by Nathalie Y. R. Agar, Ph.D., at Harvard University to test the instrument in the operating room during brain cancer surgery, comparing it with the gold standard — traditional analysis of tissue samples by pathologists.

“These procedures are among the longest of all surgical operations, and this new technology offers the promise of reducing the time patients are under anesthesia,” Cooks explained. “DESI can analyze tissue samples and help determine the type of brain cancer, the stage and the concentration of tumor cells. It also can help surgeons identify the margins of the tumor to assure that they remove as much of the tumor as possible. These are early days, but the analysis looks promising.”

The other instrument under development in Cooks’ lab is a “PaperSpray ionization” mass spectrometer. The researchers are using this new device to monitor the levels of chemotherapy drugs in patients’ blood in real time. “Many cancer drugs have relatively narrow therapeutic ranges, so they need to be in the blood at certain levels to work properly,” he noted. “But at present, that information is not obtained in real time, so a patient could end up with too little or too much of the drug in his or her body.”

Both the DESI and PaperSpray mass spectrometers work in a similar way. To weigh chemicals, mass spectrometers need to ionize, or give a positive or negative charge to a substance. Mass spectrometers usually do this inside the instrument under a vacuum without air. But DESI and PaperSpray can do this so-called ionization process out in the open. This allows scientists much more flexibility. DESI and PaperSpray also can do analyses without separating out all of the chemicals in a sample first (unlike conventional instruments), which provides quick results. They are also very easy to operate. “You just point and shoot,” said Cooks.

Currently, Cooks’ team is testing to see whether DESI can provide different information compared to what pathologists can provide by looking at human tissues under a microscope. In addition, the researchers are testing PaperSpray on patients’ blood samples, though Cooks points out that the device also could measure the levels of drugs of abuse or pharmaceuticals in urine or other body fluids.

Cooks is a co-founder of Prosolia, Inc., which sells DESI instruments. He and his long-term collaborator Professor Zheng Ouyang of Purdue University are working with QuantIon Technologies, Inc., to develop PaperSpray as a point-of-care device for use in doctors’ offices and hospitals.

The researchers acknowledged funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Institute for Biomedical Development at Purdue University.

To automatically receive news releases from the American Chemical Society contact newsroom@acs.org.

###

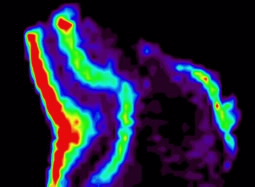

spectrometry. DESI and PaperSpray mass

spectrometers can help cancer physicians analyze

tumors and medication levels.