FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

WASHINGTON, March 23, 2023 — Diabetes used to be a death sentence, killing people by disrupting sugar metabolism. But in 1922, University of Toronto researchers and doctors successfully treated a boy who had diabetes by injecting him with insulin extracted from animal pancreases. Physicians clamored for the new drug, but the university couldn’t meet demand. So the university began collaborating with Eli Lilly & Company, which refined and scaled up production techniques and delivered the world’s first commercial doses in 1923. Since the 1920s, millions have been treated with insulin. On March 27, the American Chemical Society (ACS) will honor Lilly’s contribution to these achievements with a National Historic Chemical Landmark designation ceremony in Indianapolis.

“Chemistry plays a critical role in many aspects of everyday life, and perhaps most importantly in the development of treatments for diseases such as diabetes,” says ACS President Judith C. Giordan. “Advances in chemistry were crucial in devising the initial techniques to extract and purify insulin from animal products and later techniques to produce it from microbes. Eli Lilly & Company helped make extraction and purification possible and enabled mass production of insulin, thereby making treatment of diabetes more accessible to those who need it.”

The recorded history of diabetes stretches back 3,500 years, when symptoms were mentioned on an Egyptian papyrus. For millennia, little could be done to help people with the condition. But just over a century ago, everything changed.

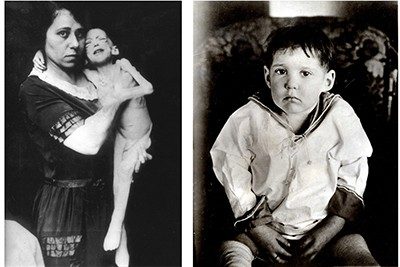

In December 1921, 14-year-old Leonard Thompson was near death. The boy had diabetes and weighed just 65 pounds. After a month in Toronto General Hospital, he wasn’t improving, so his physicians turned to an experimental treatment being developed by researchers at the University of Toronto. In January 1922, the doctors cautiously injected Thompson with pancreatic fluid extracted from cows.

The team hoped to confirm what they had already seen in animals: Insulin in the extract could regulate blood sugar. As it turned out, the injection saved Thompson’s life, marking a turning point in the treatment of the disease.

Physicians who heard about the new wonder drug were desperate to obtain it to save their own dying patients, but the university was unable to produce significant quantities. In May 1922, Lilly began collaborating with the university to scale up and commercialize insulin production from animal extracts. The effort was led by chemist George Walden.

By July, the firm had shipped its first batches of insulin for clinical testing. Lilly then devised a new method to purify the animal extract. In 1923, the company began full-scale animal insulin production based on this separation technique. This revolutionized the purity and stability of the final product, paving the way for mass production.

Collaboration and licensing agreements allowed additional companies to supply insulin, including the nonprofit Nordisk Insulin Laboratory (which later became Novo Nordisk) and Hoechst AG (a predecessor of Sanofi). Innovations followed, such as increasing purity to improve tolerance, using microbes for production, and creating beneficial analogs.

Because of these advances, millions of people have been treated with insulin since the 1920s, and a once-fatal illness has turned into a manageable chronic disease. But that’s not the end of the story, because Lilly and others continue to make improvements in this treatment, thanks to the power of chemistry.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

ACS established the National Historic Chemical Landmarks program in 1992 to recognize seminal events in the history of chemistry and to increase awareness of the contributions of chemistry to society. Past Landmarks include the invention of Polaroid instant photography, the discovery and production of penicillin, the invention of synthetic plastics, and the works of such notable scientific figures as educator George Washington Carver and environmentalist Rachel Carson. For more information, visit www.acs.org/landmarks.

To automatically receive press releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note: ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.