FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

“Lithium-Ion Battery Power Performance Assessment for the Climb Step of an Electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing (eVTOL) Application”

ACS Energy Letters

Taking flight can be stressful — especially for a lithium-ion battery that powers a drone. Too much strain on these cells causes damage and shortens a device’s overall lifespan. Research in ACS Energy Letters shows the potential to improve batteries in aerial electric vehicles that take off and land vertically. The team developed a new electrolyte to address these challenges and said the “stressed out” batteries could also have second lives in less strenuous applications.

Lithium-ion batteries (LiBs) have exploded in popularity thanks to their ability to pack a large amount of power in a relatively small and light package. But they aren’t perfect, especially when a lot of that power needs to be drawn from the battery cell in a short amount of time. For example, drones put a high strain on their batteries during takeoff. While hobby drones traditionally use lithium-ion polymer batteries instead of LiBs, the latter’s high energy density is better-suited for heavier-duty drones, such as those that deliver cargo to remote locations. To better understand how high strain events like liftoff can affect LiB stability, Ilias Belharouak, Marm Dixit and colleagues “stressed out” a set of LiBs and investigated how their performance changed.

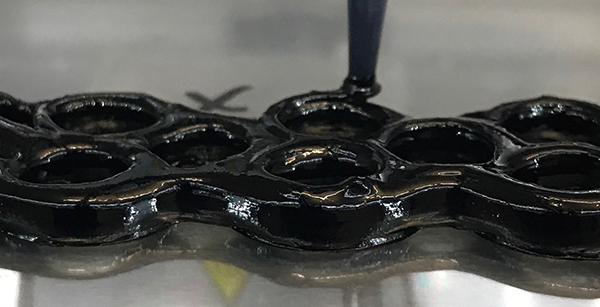

The researchers manufactured a set of LiB cells containing a specially designed, fast-charging and discharging electrolyte. Then, they drained 15 times the battery’s optimal capacity, the total amount of energy it could store, for 45 seconds. This process simulated the rapid, high-power draw, also known as a discharge, needed during vertical takeoff. After the initial discharge pulse, the cells were further drained at a more normal discharge rate and then recharged. The team found that none of the tested cells lasted more than 100 cycles under these high-stress conditions, with most starting to show decreased performance around 85 cycles.

After being “stressed,” the researchers subjected the LiB cells to a more normal, lower rate power draw. In this experiment, they observed that the cells partially retained their capacities under low-rate conditions, but failed quickly when put under rapid current drain conditions again. These results indicate that the LiBs typically used in drones might not have the characteristics necessary for long-term, high-stress usages, but they could be retired and meet more typical power demands in other applications, such as battery back-ups for power supplies and energy-grid storage. The researchers say that more work is needed to develop alternative battery technologies that are better suited for vertical takeoff and other high-power-demand applications.

The authors acknowledge funding from the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM) Army Research Laboratory. The research was performed at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive press releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note: ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.