New guidelines go beyond plagiarism and falsifying data to many other aspects, including sustainability and teamwork.

Mike May for the American Chemical Society

More than any time in recent history, ethics in science now gets as much—maybe more—media attention than results. Although most scientists always focused on ethical behavior, the community continues to improve this element of training programs. As one example, the American Chemical Society’s Committee on Professional Training (CPT) developed minimum requirements, included in the 2023 Guidelines for ACS Approval, for training students in ethics and professional conduct.

In terms of ethics, all scientists know the basics: don’t plagiarize or doctor data. Nonetheless, the ACS Guidelines include those elements and others, including appropriately documenting data, using that data responsibly, citing the work of others where appropriate, and maintaining scholarly standards in publishing results.

For professional conduct, the ACS guidelines zoom in on the daily life of a scientist and how to work with the community. “Preparing students for the modern workplace requires more than technical skills,” as noted in the ACS guidelines. “Surveys of employers consistently indicate the importance of interpersonal skills such as complex communication, social skills, teamwork, cultural sensitivity, and dealing with diversity for success in a wide range of areas.” So, the ACS guidelines encourage future chemists to develop a range of skills, from clear communication and working with a team to considering the economic, environmental, moral, political, and social factors connected to new chemical knowledge.

The question is: What’s the best way to incorporate these requirements in chemistry programs for undergraduates?

Beyond the basics at Bemidji

In far north Minnesota, about 10–20 chemistry majors graduate from Bemidji State University every year. For those students, says Keith Marek, chemistry department chair at Bemidji, “regardless of whether they get a job in chemistry or not, they’re going to be working with other people—whether it be in a small analytical lab or a larger setting or teaching or whatever.” As a result, “it is important that they learn to conduct themselves professionally,” he says. As one example, Marek points out: “They might be in a diverse setting, so they need to respect the diversity of others.”

On the ethics side, Marek emphasizes the careful handling of data. “When they’re collecting and reporting their data, they need to be honest, accurate, and represent the data fairly,” he says.

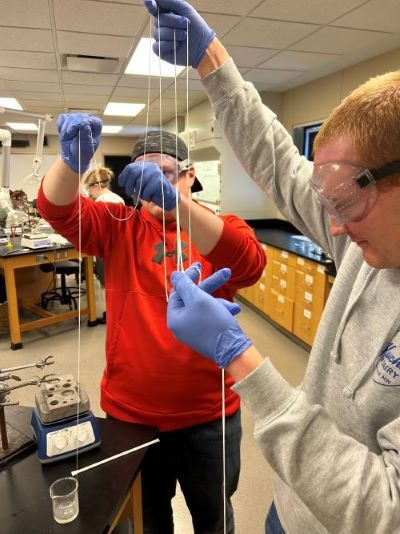

Even first-year students at Bemidji start to learn about ethics and professional conduct in science. As an example, Marek says: “At the freshman level, they have library assignments where they’re learning how to cite the work of others.” Plus, the students learn how to put data in tables or graphs. “They’re expected to use those skills when they’re writing their lab reports that first year, so they professionally present the information,” Marek explains.

In upper-level chemistry classes at Bemidji, students learn more about handling their own data. As examples, Marek mentions keeping an accurate lab notebook and “making sure that they record all of their data and observations.” In analyzing that data, students learn about ethical approaches. For instance, Marek discusses statistical analysis and using mathematical tests in conjunction with observations made in the lab to determine if a data point is an outlier.

Part of professional conduct involves sharing information with other scientists. To help chemistry undergraduate students at Bemidji learn that skill, they give presentations in seminar courses. Here, the students prepare and present information. Plus, Bemidji runs a local student achievement conference where students can fine tune their presentation capabilities. “At a minimum, our students might present at that conference,” Marek says. “But some of them doing research might be presenting at regional and national meetings, too.”

So, from start to finish, a Bemidji chemistry major learns about ethics and professional conduct—often learning by application and example. As Marek concludes, these skills “go all throughout the curriculum.”

Important elements for industry

Although someone with an ACS-approved undergraduate degree in chemistry could pursue many career paths, many of those opportunities exist in a wide range of industries. Just like other fields, an industrial chemist’s success will depend on ethical and professional conduct.

“When we think about the people who we’re hiring from academia, we want to ensure that they have the skills and the professional training within universities so the students are well-equipped to serve within industry,” says Matthew Irwin—chair of ACS Philadelphia, an associate member of CPT, and a principal investigator at DuPont. “That was an important passion point for me,” he says. That’s why he accepted an invitation to join CPT.

In some ways, Irwin sees his ACS role as more important than ever. “I work in an area where science isn’t maybe as trusted as it used to be,” he says. “So, I think that having strong ethics, strong foundations really helps to build a lot of the public trust in science and helps us to communicate that as well.”

As a key training element, Irwin talks about teamwork. “A lot of times in school, you may be working individually on assignments,” he says. “As soon as you get to industry, you’re immediately working on teams, working with other people.” He encourages undergraduate chemistry programs to teach these skills “so that you’re ready to hit the ground running when you get into the industry.”

That teamwork also depends on respecting colleagues. “At a college, you have some experience meeting people from different backgrounds, but as soon as you work for a company—especially a multinational company—understanding how different people work and how to interact with them in a way that makes sure you have good respect for people is critical,” Irwin explains.

In addition, Irwin endorses the use of case studies, especially ones where something went wrong. “Maybe there were concerns around ethics or concerns around bookkeeping that led to a major disaster,” he says. “Students should be made are aware of how it happened.”

Keep it sustainable

Although a sustained effort ensures that undergrads learn about ethics and professional conduct, the ACS Guidelines also encourage teaching students about sustainability in science. Deborah Bromfield Lee, associate professor of chemistry at Florida Southern College and an associate member of CPT, is particularly interested in sustainable practices.

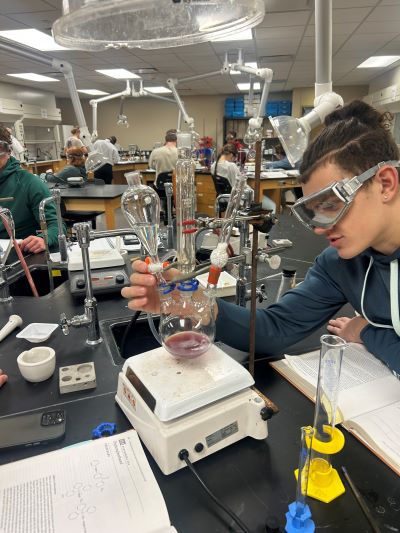

In one class that she was teaching, Lee used a hands-on approach to sustainability. “I decided to have students kind of discover on their own by keeping track of all their waste in my class,” she says. “Some of the students became a little bit more cognizant of when they did certain things.” As an example, she mentions pipettes. “If they’re taking the same chemical solution over and over, do they need a new pipette every time?” She asks. “Some of them started to just put a pipette in the beaker and use it the next time they needed the solution.”

By including sustainability in the ACS Guidelines, Lee says, “we can get students involved by introducing them to the idea.” As an example, she asks students: “What can we do to reduce our waste, and how would that impact our lab and other people?”

To teach students the value of ethics and professional conduct, “you have to be intentional,” says Lee. That’s just what the ACS Guidelines will bring to undergraduate chemistry training.