Bill Carroll, Carroll Applied Science, LLC

Bill Carroll holds a PhD from Indiana University, where he is currently an adjunct professor of chemistry and heads his own company, Carroll Applied Science, consulting for industry and intergovernmental organizations. Bill was ACS President (2005), Chair of the Board (2012-14) and is a Fellow of ACS, AAAS and the Royal Society of Chemistry. He holds two patents, has published four books and has more than 80 publications in the fields of organic electrochemistry, polymer chemistry, combustion chemistry, incineration, plastics recycling… and popular music history and chart analytics.

I’ve always felt that the guy who dies with the best stories wins. Over the course of the last nearly 50 years since I decided chemistry was my professional home, I’ve been blessed with so many great stories that I’m pretty sure I’ve made it into the medal round.

There was the time I found myself locked out of my room in DC in a hotel lobby waiting in line to speak to someone at the front desk at 12:15 AM … in my pajamas. There was the day the President of the City Council threw me out of Pittsburgh. Or the time I saw the famous Moscow subway dogs who know where they’re going in the city and let themselves on and off the trains at regular times during the day. Got food poisoning on that trip, too.

But there really isn’t time to tell all those stories today.

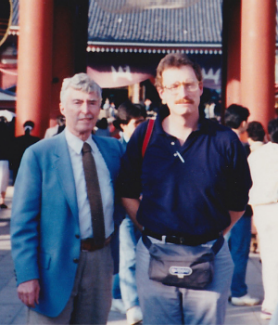

Today I want to talk about the single smartest thing I ever did in my career, and it involved travel to Wuxi, China, in 1988 to start up the first plant we licensed. I was the lead of the away team and I decided to take my father along with us. He was a bomber pilot in China in 1944 and 1945 during World War II in a combined US and Chinese unit, and this was his first trip back to the mainland.

Those of you who know me may think of me as having a bit of a personality, but I pale in comparison to my father. He could talk to anybody, and usually did. And as someone who contributed to the war effort to aid the Chinese, he became an instant hit in Wuxi.

Because of travel schedules for our corporate dignitaries, we had to have the banquet celebrating our successful implementation of the technology before we actually even started the project. Dad was there at the dinner, regaling our Chinese partners with war stories of the US 14th Army Air Corps in western China. He was only in China for a year and based on his stories—which I had heard over and over for 35 years--he remembered every waking moment.

Chinese banquets are a mixed pleasure. Naturally, there is course after course of food, most of it good. The single most useless question to ask is “What is this?” If it tastes good, eat it. If not, above all, do not make the American mistake of cleaning your plate to get it over with. That just signals you loved it and want more.

Then there’s the alcohol. Known as baijiu, or in some cases the specific type, maotai, it is a ceremonial liquor distilled from sorghum, drunk in shots after flowery toasts. It clocks in at about 60% ethanol and tastes like dirty socks soaked in Old Spice. I found the Chinese custom was to go around the table and individually toast the guests personally, such that at the end of round one, the hosts had each had one shot and the guests about eight.

My father, no stranger to either alcohol or flowery toasts, picked up the rhythm immediately, offering dedications of his own. But I had to start the project at 0-dark-30 the next morning, and I was plenty nervous about that. So I wanted him to back the activity down a little, because of course I had to drink to his toasts. He looked at me and said, “Wotsa matter, Billy? Can’t you take it?”

Sadly, the answer was no, but further embellishment will be left to your imagination.

Our project would have us there for about a month. During that time, the people at the plant set Dad up with a driver and an interpreter and put him on a car and riverboat tour of southeastern China, which he loved. This was our first licensing job and we were guessing at some of the milestones we committed to in the contract. And in fact, we missed a couple. Our Chinese partners could have held us to those, but because they were only minor flaws, and due nearly totally to my father’s diplomacy they said, ”Eh, it’s OK.”

And that was why I called this my smartest business decision ever. Make no mistake: I was gratified to have my father see me at work to let him know I turned out OK. But the benefit to the company was instead of haggling over a couple of trivial missed specifications and potential monetary givebacks, we skated, largely because of the ambassador and insurance policy I brought along.

Between 1988 and 2002 (when he passed away), he made a couple more trips back to China for reunions with his Chinese and American war buddies, one of whom is still alive today at age 102. My career would take me back there a number of times, the most recent just before the pandemic. Every trip was an experience, but none was like traveling with the old man. He either had, or inspired the best stories. Clearly, he won.

This article has been edited for length and clarity. The opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the view of their employer or the American Chemical Society.