FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | August 21, 2016

Stopping scars before they form

Note to journalists: Please report that this research is being presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

Canceled:

A press conference on this topic will be held Monday, Aug. 22, at 2:30 p.m. Eastern time in the Pennsylvania Convention Center. Reporters may check in at Room 307 in person, or watch live on YouTube http://bit.ly/ACSlivephiladelphia. To ask questions online, sign in with a Google account.

PHILADELPHIA, Aug. 21, 2016 — Most people start racking up scars from an early age with scraped knees and elbows. While many of these fade over time, more severe types such as keloids and scars from burns are largely untreatable. These types of scars are associated with permanent functional loss and, in severe cases, carry the stigma of disfigurement. Now scientists are developing new compounds that could stop scars from forming in the first place.

The researchers are presenting their work today at the 252nd National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS, the world’s largest scientific society, is holding the meeting here through Thursday. It features more than 9,000 presentations on a wide range of science topics.

“The treatment we’re developing is focused on the major needs of patients with burns, keloids and Dupuytren contracture, a hand deformity,” says Swaminathan Iyer, Ph.D. “These patients have extensive scarring, which can impair their movements. There are no current treatments available for them, and we want to change this.”

Burns lead to the hospitalization of tens of thousands of people in America every year, according to the American Burn Association. About 250,000 U.S. patients undergo surgical treatment annually for keloids, which are firm, overgrown scars, and for other types of excessive scarring, Iyer says. And a survey by RTI International found that an estimated 7 percent of Americans have Dupuytren contracture, a hand condition that develops when the connective tissue under the palm’s skin contracts and toughens over time.

To help prevent such conditions, Iyer and colleagues at The University of Western Australia, Fiona Wood Foundation and Royal Perth Hospital Burns Unit, together with Pharmaxis Ltd., (all in Australia) are studying compounds that inhibit an enzyme called lysyl oxidase, or LOX. During scar formation, this enzyme enables the collagen involved in wound healing to crosslink. This bonding underpins the fundamental biochemical process leading to scar formation, Iyer says.

“During the scarring process, the normal architecture is never restored, leaving the new tissue functionally compromised,” he explains. “So our goal is to stop the scar from the beginning by inhibiting LOX. We have been fortunate to work in collaboration with the pharmaceutical company Pharmaxis, which is designing novel and highly selective small molecules that will allow the establishment of normal tissue architecture after wound repair.”

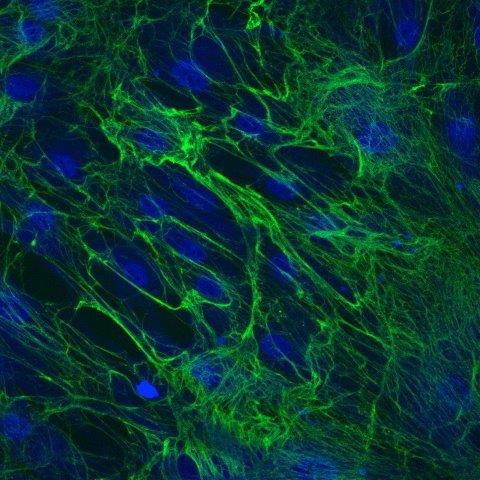

The team tested their molecules using a “Scar-in-a-jar” model, which mimics scar formation. In short, this technique involved culturing human fibroblasts from scar tissues in a petri dish. The cells overproduce and secrete collagen, as they would in a real injury. In the study, the researchers added LOX inhibitors to cultures from patients with Dupuytren’s, keloids and other scar tissue, and detected changes using two-photon microscopy combined with biochemical and immunohistochemical analyses.

“The preliminary data strongly suggest that lysyl oxidase inhibition alters the collagen architecture and restores it to the normal architecture found in the skin,” Iyer says. “Once the in-vitro validation has been done, the efficacy of these compounds will be tested in pig and mouse models. Depending on the success of the animal studies and optimal drug candidate efficacy, human trials could be undertaken in a few years.”

The researchers’ primary objective is to help patients with severe or extensive scarring, but Iyer says that the inhibitors could potentially be used for cosmetic purposes as well.

Iyer acknowledges funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, The University of Western Australia and Pharmaxis Ltd.

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. With nearly 157,000 members, ACS is the world’s largest scientific society and a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences. Its main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Media Contact

ACS Newsroom

newsroom@acs.org

High-resolution image