FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | March 20, 2018

Making fragrances last longer

Note to journalists: Please report that this research will be presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

A press conference on this topic will be held Tuesday, March 20, at 1 p.m. Central time in the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center. Reporters may check-in at the press center, Great Hall B, or watch live on YouTube http://bit.ly/ACSLive_NOLA. To ask questions online, sign in with a Google account.

NEW ORLEANS, March 20, 2018 — From floral perfume to fruity body wash and shampoos, scents heavily influence consumer purchases. But for most, the smell doesn’t last long after showering before it fades away. Scientists have now developed a way to get those fragrances to stick to the skin longer instead of washing down the drain immediately after being applied.

The researchers are presenting their results today at the 255th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS, the world’s largest scientific society, is holding the meeting here through Thursday. It features more than 13,000 presentations on a wide range of science topics.

“Companies incorporate a lot of fragrance oils in wash-off products, such as face washes and body scrubs, but the majority of these oils get washed away,” Martin S. Vethamuthu, Ph.D., says. “My research team of solvers wants to help other companies amplify the efficacy, add to the allure and ensure the integrity of the retention of these fragrance notes in their products for skin and hair.”

Vethamuthu explains that after consumers take a shower, they want their friends and loved ones to notice whatever scent they are wearing. This is why consumers are willing to spend a lot of money on these products but many are left dissatisfied and disappointed because the scent doesn’t even last the average time of a commute.

The goal of this research is to increase the efficiency of the fragrance oils. Fragrance oils are expensive, and maintaining a scent is a complex process. “To build a scent profile in a body wash, it is a creative and artistic process of blending the fragrances,” Vethamuthu, who is at Ashland, says. There are three categories, the top note, middle note and base note. “Each of these has a purpose, and some scents are meant to evaporate during the shower while others are meant to remain on the skin even after toweling off,” he says. These factors play a critical role in determining whether a consumer will repurchase a product.

To develop fragrance profiles, researchers use panels of people who have an exceptional sense of smell. But this practice is time consuming and costly. Every time a technician blends a fragrance, the oil is sent to evaluators. Each change made to the perfume means the formula must be remade and re-evaluated by the panelists until the final product is perfected. In addition, the evaluators provide an impression of the overall fragrance, so they might miss some faint fragrance notes.

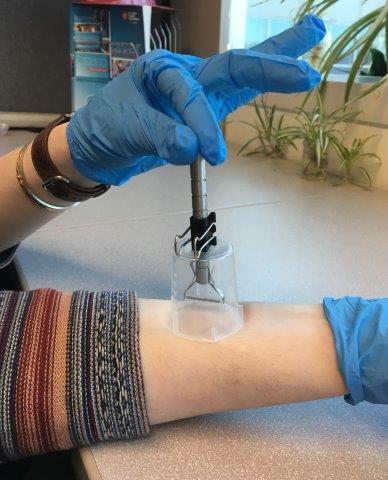

To overcome this challenge, Vethamuthu is reporting that his group has adapted a device known as the twister bar headspace sorption extraction sensor, commonly used in the food industry to detect chemicals that could contribute to off-flavors or scents. The sensor absorbs trace amounts of volatile fragrances deposited on the skin after a shower. Combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, the team can gather a profile of the scents that remain on skin after rinsing off. Then, fragrance evaluators are only brought in at the last step to validate and verify the results.

Vethamuthu also looked at ways to ensure the fragrances lasted longer by mixing them with various polymers, which help the scents remain on the skin. “Polymers impact different fragrances in diverse ways,” he says. “By studying synthetic and naturally derived polymers, manufacturers can select the types of polymers they want to use that will correspond with the fragrance notes they want to prevail.” Vethamuthu’s group used the sensor to assess which fragrances still lingered on the skin several hours after the scents were applied.

But there was a lot of trial and error to get to this point, since companies use many different combinations of scents, and the identities of those compounds are often kept secret. “It’s a difficult process because many manufacturers do not want to share their perfume formulas in detail,” Vethamuthu states. “If you don’t know what to look for going in, then you will never be able to determine which polymers would work best.” As a result, he works closely with the manufacturers to pry as much information from them as he can. If he knows the precise perfume formula, he can tailor the polymers for the manufacturer. Increasing the retention can mean that manufacturers won’t need to add as much fragrance oil, which could lead to lower costs for both the industry and consumers.

Vethamuthu plans to continue to optimize and refine these methods. He also hopes to validate the instrumental values with the actual sense of smell.

Vethamuthu’s work was funded by Ashland.

The American Chemical Society, the world’s largest scientific society, is a not-for-profit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS is a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences. ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies. Its main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Media Contact

ACS Newsroom

newsroom@acs.org

High-resolution Image