FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

ACS News Service Weekly PressPac: January 19, 2022

Camels’ noses inspire a new humidity sensor

Camels have a renowned ability to survive on little water. They are also adept at finding something to drink in the vast desert, using noses that are exquisite moisture detectors. In a new study in ACS Nano, researchers describe a humidity sensor inspired by the structure and properties of camels’ noses. In experiments, they found this device could reliably detect variations in humidity in settings that included industrial exhaust and the air surrounding human skin.

Humans sometimes need to determine the presence of moisture in the air, but people aren’t quite as skilled as camels at sensing water with their noses. Instead, people must use devices to locate water in arid environments, or to identify leaks or analyze exhaust in industrial facilities. However, currently available sensors all have significant drawbacks. Some devices may be durable, for example, but have a low sensitivity to the presence of water. Meanwhile, sunlight can interfere with some highly sensitive detectors, making them difficult to use outdoors, for example. To devise a durable, intelligent sensor that can detect even low levels of airborne water molecules, Weiguo Huang, Jian Song, and their colleagues looked to camels’ noses.

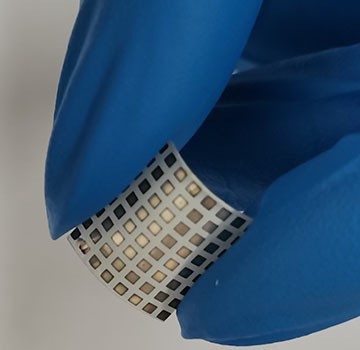

Narrow, scroll-like passages within a camel’s nose create a large surface area, which is lined with water-absorbing mucus. To mimic the high-surface-area structure within the nose, the team created a porous polymer network. On it, they placed moisture-attracting molecules called zwitterions to simulate the property of mucus to change capacitance as humidity varies. In experiments, the device was durable and could monitor fluctuations in humidity in hot industrial exhaust, find the location of a water source and sense moisture emanating from the human body. Not only did the sensor respond to changes in a person’s skin perspiration as they exercised, it detected the presence of a human finger and could even follow its path in a V or L shape. This sensitivity suggests that the device could become the basis for a touchless interface through which someone could communicate with a computer, according to the researchers. What’s more, the sensor’s electrical response to moisture can be tuned or adjusted, much like the signals sent out by human neurons — potentially allowing it to learn via artificial intelligence, they say.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Fujian Science and Technology Innovation Laboratory for Optoelectronic Information of China, Fujian Institute of Research on the Structure of Matter, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive press releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note: ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.

Media Contact

ACS Newsroom

newsroom@acs.org

View larger image