FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

“Technological Properties of Orange Sweet Potato Flour Intended for Functional Food Products as Affected by Conventional Drying and Milling Methods”

ACS Food Science & Technology

Orange, starchy sweet potatoes are great mashed, cut into fries or just roasted whole. But you likely haven’t considered grinding them into a flour and baking them into your next batch of cookies — or at least, not yet! Recent research published in ACS Food Science & Technology has reported the best method to turn sweet potatoes into gluten-free flours that are packed with antioxidants and perfect for thickening or baking.

Wheat flour has been used for tens of thousands of years, and likely isn’t going away anytime soon. But for those who face gluten intolerance or have celiac disease, the gluten proteins in wheat flour can lead to stomach pain, nausea and even intestinal damage. Several gluten-free options are either already available or in development, including those made from banana peels, almonds and various grains. But an up-and-coming contender is derived from sweet potatoes, as the hearty tuber is packed with antioxidants and nutrients, along with a slightly sweet flavor and hint of color.

Before it can become a common ingredient in store-bought baked goods, the best practices for processing the flour need to be established. Though previous studies have investigated a variety of parameters, including the way the potatoes are dried and milled, none have yet determined how these different steps could interact with one another to produce flours best suited for certain products. So, Ofelia Rouzaud-Sández and colleagues wanted to investigate how two drying temperatures and grinding processes affected the properties of orange sweet potato flour.

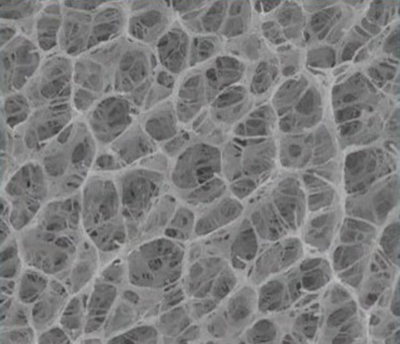

To create their flours, the team prepared samples of orange sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) dried at either 122 or 176 F then ground them once or twice. They investigated many parameters for each sample, comparing them to store-bought sweet potato flour and a traditional wheat one. Regardless of drying temperature, grinding once damaged just enough of the starch to make it ideal for fermented products, such as gluten-free breads. Grinding twice further disrupted the starch’s crystallinity, producing thickening agents ideal for porridges or sauces. When baked into a loaf of bread, the high-temperature-dried, single-ground sample featured higher antioxidant capacity than both the store-bought version and the wheat flour. The researchers say that these findings could help expand the applications for orange sweet potato flour, both for home cooks and the packaged food industry.

The authors acknowledge funding from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) under Research Grant B-S-3869 and the Universidad de Sonora.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1876 and chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS is committed to improving all lives through the transforming power of chemistry. Its mission is to advance scientific knowledge, empower a global community and champion scientific integrity, and its vision is a world built on science. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, e-books and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Registered journalists can subscribe to the ACS journalist news portal on EurekAlert! to access embargoed and public science press releases. For media inquiries, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note: ACS does not conduct research but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.