FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

“Calcium Tungstate Microgel Enhances the Delivery and Colonization of Probiotics during Colitis via Intestinal Ecological Niche Occupancy”

ACS Central Science

Probiotics can help maintain a healthy gut microbiome or restore populations of “good bacteria” after a heavy course of antibiotics. But now, they could also be used as an effective treatment strategy for certain intestinal diseases, such as Crohn’s disease. Researchers reporting in ACS Central Science have developed a microgel delivery system for probiotics that keeps “good” bacteria safe while actively clearing out “bad” ones. In mice, the system treated intestinal inflammation without side effects.

In the digestive system, there’s a delicate balance of bacterial populations. When this balance is disrupted, bad bacteria can take over the colon, causing it to swell, resulting in colitis. Certain diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and Crohn’s disease, involve chronic colitis and currently require immunosuppressants to treat them. These drugs are expensive and non-specific, sometimes giving rise to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

An alternative strategy is to deliver beneficial bacteria, or probiotics, to help restore balance. But to reach the colon, a treatment must first pass through stomach acid, withstand being cleared out by the intestine, then fight for space alongside the numerous invading bacteria. Pairing probiotics with a drug delivery system could make this strategy feasible, though most current approaches simply protect the probiotics from digestion without affecting the microbes responsible for the condition. So, Zhenzhong Zhang, Junjie Liu, Jinjin Shi and colleagues wanted to combine probiotics with specialized microgel spheres that could not only protect the good bacteria, but also actively help clear out the bad.

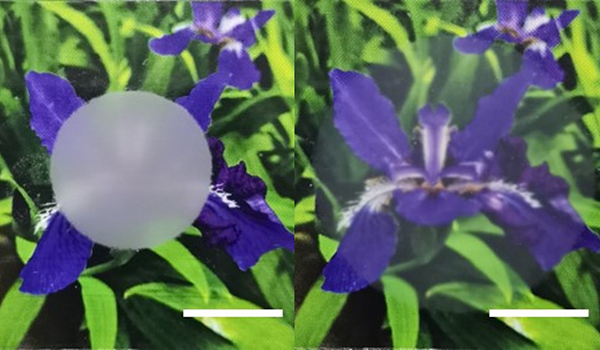

To create their system, the researchers combined sodium alginate, tungsten and calcium-containing nanoparticles into small, spherical microgels, then coated them with beneficial, probiotic bacteria. The gels protected the bacteria as they made their way through the stomach and increased their retention time in the colon. Once there, calprotectin proteins — highly expressed during colitis — bound to the calcium and disassembled the gels, allowing the tungsten to escape. By displacing molybdenum in a key enzyme substrate of the bad bacterium Enterobacteriaceae, tungsten inhibited the microbe’s growth while leaving the probiotics unaffected. In experiments using a colitis mouse model, the system allowed probiotics to proliferate in the intestine without any side effects. Additionally, mice with the microgel spheres did not exhibit many of the hallmarks of colitis, such as shortened colons or damaged intestinal barriers, showing that the delivery system could be a viable treatment strategy. Though the researchers also want to prove its utility in more advanced preclinical models, they say that this work provides a new perspective into treatments using colonizing probiotics.

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Henan Province and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive press releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Note: ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.