Al and Helen Free and the Development of Diagnostic Test Strips

Dedicated May 1, 2010, at ETHOS in Elkhart, Indiana.

It is difficult to recall a time when doctors and patients had trouble tracking the presence of glucose and other substances in urine and blood. Lack of sufficient measurement tools made it difficult to manage a host of diseases, including diabetes as well as other metabolic diseases and kidney and liver conditions. Today, self-management of these diseases is an easier process because of the development of diagnostic test strips by Alfred and Helen Free and their research team at Miles Laboratories.

Contents

Origins: Early Diagnostic Test Strips

In 1938 Dr. Walter Ames Compton joined Miles Laboratories in Elkhart, Indiana, a company best known for Alka-Seltzer®. Miles’s executives wanted the company to discover a “wonder drug,” allowing the firm to move into the lucrative prescription drug business. Compton had other ideas.

From his experience as an intern at Billings Hospital in Chicago, Compton appreciated the inadequacy of existing tests for probing the chemical makeup of a patient’s urine. Benedict’s reagent was the primary test for the presence of glucose in urine, an indication of diabetes. Urine was mixed with the reagent in a test tube, then heated over a Bunsen burner. A change in the color of the solution from blue to yellow, orange, or red indicated the presence of sugar. The extent of the color change allowed for an estimate of the amount of sugar in the urine.

The procedure was not very accurate, and Compton, as head of research and development, pushed for the development of a more convenient and precise test. Building on Miles’ experience with Alka-Seltzer, Compton and a colleague, Jonas Kamlet, searched for a method to put reagents in an effervescent tablet that could determine the presence and amount of sugar when placed in a test tube of urine. The scientists succeeded, and in 1941 Miles introduced the effervescent tablet Clinitest®.

Clinitest contained cupric sulfate, sodium hydroxide, and citric acid mixed with a bit of carbonate to make it fizz. The presence of glucose in urine could be measured by adding a few drops of urine to a Clintest tablet in a test tube and charting differences in color. Clinitest more accurately measured the amount of glucose present than previous tests, making it an early and effective diagnostic tool, and it could be performed and read in a doctor’s office or hospital.

Clinistix®: The First Dip & Read Test

In 1946 Alfred Free joined the Ames Division of Miles Laboratories to set up a biochemistry division. Free had a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Western Reserve University and additional research experience at the Cleveland Clinic. He assembled a research team, and a young woman working as a quality control chemist at Miles interviewed for a position. Free hired Helen Murray, and in 1947 they married, starting a long personal and professional relationship.

Free’s team improved Clinitest by making it more sensitive, then turned to a second key test for diabetes, using nitroprusside to detect ketones. This resulted in Acetest®. After several more innovations, Free wondered if there were a better way to do the test. Helen Free remembers: “It was Al who said, ‘You know, we ought to be able to make this easier and even more convenient than tablets, so no one would have to wash out test tubes and mess around with droppers.’”

Free assumed that analytes in urine could be detected on a strip of paper containing reagents that produced color changes. Free’s team also knew that Clinitest detected the presence of any sugar, not just glucose. That diminished the utility of Clinitest for doctors who needed to measure specifically the presence of glucose in urine. The second challenge for the Free team was to embed the reagents on a filter paper strip. The result was dip-and-read Clinistix®, the first test specific for glucose, released in 1956. The researchers used a double sequential enzymatic reaction: glucose oxidase and peroxidase. The process was very labor intensive. Researchers cut the filter paper, dipped it into reagent solutions, and dried the paper in ovens.

He [Al Free] said, ‘Well, instead of doing it that way, we could get rid of the dropper, if we just dipped the paper into the urine.’ That’s what started it.”

—Helen Murray Free, interview by James J. Bohning in Elkhart, Indiana, 14 December 1998 (Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Foundation, Oral History Transcript #0176)

Multiple Tests

In 1957 Miles introduced Albustix®, a dip-and-read test for protein in urine. The company now had diagnostic procedures for the two most common urine tests. Other tests followed. The development of additional diagnostic tests led to another breakthrough: combining reagents for two or more tests on one strip as a further convenience for the user.

Combining two reagents on one strip required creating a water-impervious barrier between the reagents on the paper to prevent the reagents from running together and compromising results. Uristix®, released in 1957, combined tests for glucose and protein. In the 20 years that followed, Miles developed and manufactured reagents to measure ketones, blood, bilirubin, urobilinogen, protein, nitrite, urinary leukocytes, and pH. The Frees became recognized experts in the field of urinalysis and published several texts and monographs.

Instrument-Based Fingertip Blood Testing

Urine testing does not provide a real-time picture of blood glucose levels since glucose levels in urine lag behind those in blood. In 1964, Miles released Dextrostix®, reagent strips for testing blood glucose. Five years later Miles introduced the Ames Reflectance Meter® (ARM), invented by Anton Clemens. Bulky and heavy by modern standards, and powered by a lead-acid battery, the analog device was the first portable blood glucose meter.

Although marketed for use by professionals, the ARM proved effective for patient self-testing. Later improvements by numerous companies included optically read test strips, electrochemical strips, the ability to test capillary blood from anatomical sites other than the fingertips, and continuous blood glucose monitors. Today, self-management of blood glucose is common clinical practice in the management of diabetes.

In the end, Miles Laboratories never discovered its “wonder” drug, but, as Helen Free says, “they sure went hog wild on diagnostics, and that’s all Al’s fault. He was the one who pushed diagnostics.”

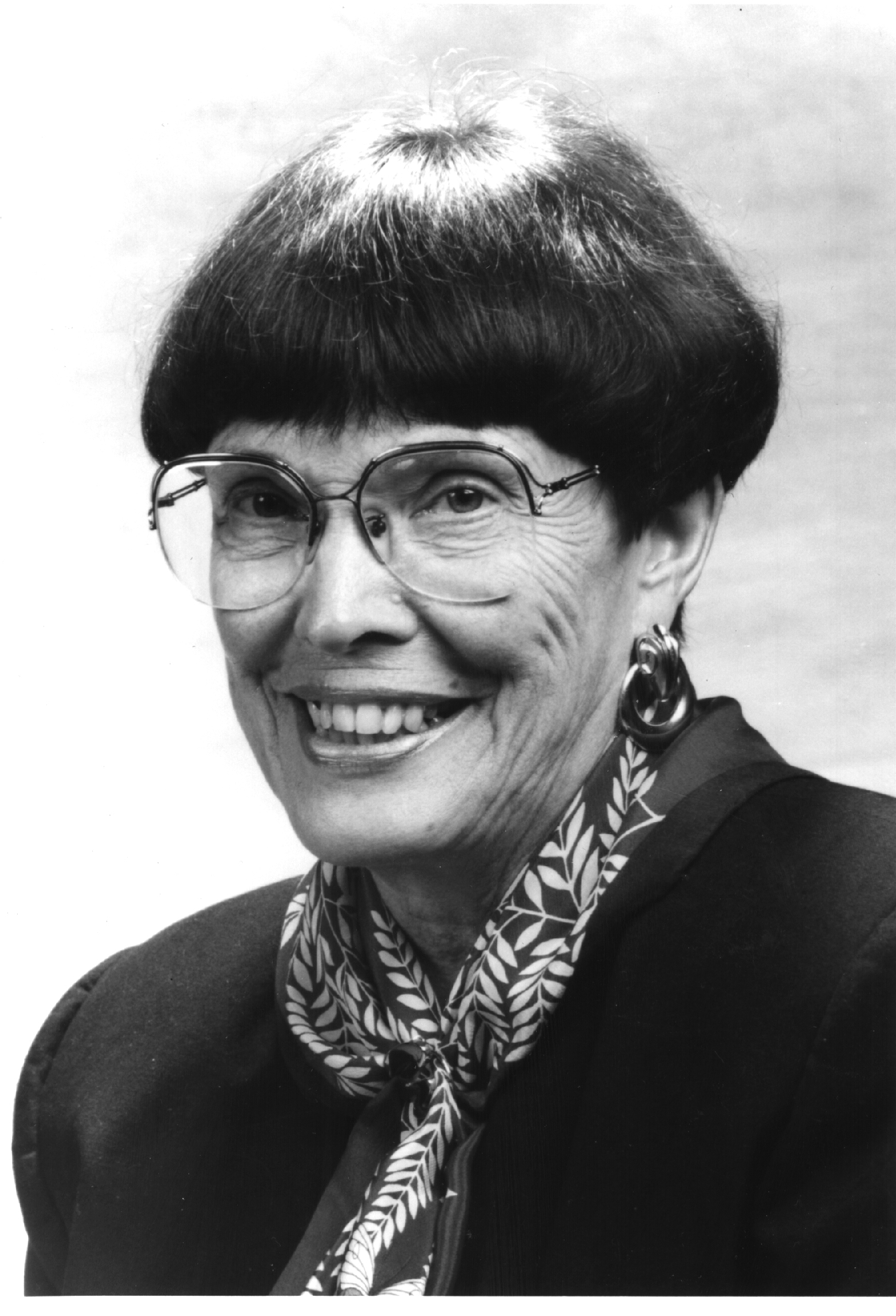

Helen M. Free Biography

Helen Mae Murray was born in 1923 in Pittsburgh, the daughter of James Murray, a coal company salesman, and Daisy Piper Murray, who died in an influenza epidemic when Helen was six. The family moved to Youngstown, Ohio, when Helen was three. One of her earliest recollections is accompanying her father, “a real wonderful guy,” on his rounds as he sold coal to dealers who in turn sold to homes.

Helen attended Youngstown public schools through the sixth grade, moving to the suburb of Poland for the seventh grade, where she finished elementary school and high school and where she received straight “A’s.” So did another female student, but because her father could afford to send her to college, the school arbitrarily designated the other student valedictorian and Helen salutatorian. “I didn’t think it was very fair,” she remembers, “but what could I do about it?”

Free had exposure to chemistry and physics in high school, but she intended to be a Latin and English teacher when she entered the College of Wooster in September 1941. That changed after Pearl Harbor, when the housemother announced that with all the men gone to war, the “girls” should take science. She turned to Free and said, “Helen, you’re taking chemistry, aren’t you? Why don’t you switch [majors]?” Reflecting on her decision to agree with the housemother, Free observes, “Just like that! I think that was the most terrific thing that ever happened because I certainly wouldn’t have done the things I’ve done in my lifetime.”

Free took the requisite chemistry courses, and upon graduation landed an interview at Miles Laboratories. She went to Elkhart for the interview and remembers being crammed in a car with three or four men who were going to lunch at the Friday Club, which did not admit women, so they dropped her off at the YWCA. Though she did not get lunch, she was offered a job in the control laboratory testing ingredients for vitamins.

After a few years in the control laboratory, Helen joined her future husband’s research team, a move that satisfied her wish to do research. Al and Helen, who married in 1947, became lifelong research partners as well.

Research at first turned out to be less than Helen Free had anticipated. It was, she remembers, “just as routine as quality control… I did bilirubins all day long, day in and day out.” On the other hand, Free found it “kind of neat”, because the work aimed to discover a new antibiotic. Unfortunately, the effort failed.

Helen Free retired in 1982 but continued as a consultant with what is now Bayer HealthCare LLC through 2007. She has remained active as a champion of science education and outreach. Free chaired the National Chemistry Week task force of the American Chemical Society for five years, and in 1993 she was elected president of the Society, using her post to raise public awareness of the contributions of chemistry to modern life. The ACS created an award in her honor, the Helen M. Free Award in Public Outreach. In 2000, Helen and Al Free were inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Al and Helen had six children together. Al Free died in 2000.

Further Reading

- ETHOS Science Center

- Helen M. Free and Alfred Free (Chemical Heritage Foundation)

- Oral History of Helen M. Free (Chemical Heritage Foundation)

Landmark Designation and Acknowledgments

Landmark Designation

The American Chemical Society dedicated development of diagnostic test strips as a National Historic Chemical Landmark in a ceremony at ETHOS in Elkhart, Indiana, on May 1, 2010. The text of the plaque commemorating the development reads:

A Miles Laboratories research team led by Alfred and Helen Free developed the first diagnostic test strip, Clinistix®, for detecting glucose in urine. Reagent-impregnated strips changed color based on the concentration of glucose. This breakthrough led to additional dip-and-read tests for proteins and other substances. Subsequently, researchers devised a method to combine several tests on one strip to provide healthcare professionals with simple, immediate tools to aid in the detection of disease. These innovations, along with instrument-based measurement of glucose in fingertip blood, provided patients with inexpensive means to aid in the management of diabetes and kidney disease, significantly improving their quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Adapted for the internet from “The Development of Diagnostic Test Strips,” produced by the National Historic Chemical Landmarks program of the American Chemical Society in 2010.

Quotations are taken from the following: Helen Murray Free, interview by James J. Bohning in Elkhart, Indiana, 14 December 1998 (Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Foundation, Oral History Transcript #0176).

Alka-Seltzer, Multistix, Clinistix, Acetest, Uristix, Ketostix, and Albustix are registered trademarks of Bayer HealthCare LLC.

Clinitest and Clinitek are registered trademarks of Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc.

Dextrostix was a registered trademark of Bayer Corporation.

Back to National Historic Chemical Landmarks Main Page.

Learn more: About the Landmarks Program.

Take action: Nominate a Landmark and Contact the NHCL Coordinator.