Downloads:

Odds are you’ve eaten cilantro recently. Cooks sprinkle the green leaves on tacos and guacamole or mix them into curries, Pad Thai and many dressings and sauces. In these recipes, cilantro adds a wonderfully fresh flavor that is sometimes described as lemony and peppery or bright and floral—for most of us.

However, some people despise it. Cilantro haters most often say it tastes soapy. But they may also describe its flavor as reminiscent of dead bugs or something else unappetizing.

Whether you find cilantro—sometimes referred to as coriander leaves—delicious or disgusting, you are reacting to flavorful chemicals that the plant produces. The same is true for other foods: People react very differently to the same chemistry. But why?

Before exploring the chemical reasons, we should note that our experiences with food shape our perception of it, and this perception can change over time. If you grew up eating meals containing cilantro with your family, you are more likely to have learned to enjoy it. But if you’ve recently gotten sick after eating something that contained cilantro, you may have learned the opposite lesson and acquired a dislike for it.

However, scientists have long suspected that factors such as cultural background and personal experiences don’t fully explain the strong reactions cilantro provokes.

The Chemical Senses

Two senses—smell and taste—make it possible for you to perceive flavor in your food. They rely on specialized protein receptors in the lining of the open spaces behind your nose and on your tongue’s taste buds that bind to specific molecules and trigger a response within the cells. Your nerves relay this information to your brain, which interprets it. This is how you smell cut grass or gasoline, taste strawberries or sour milk.

When you chew food, it releases molecules that waft to the back of the throat and into the space behind your nose, where smell receptors detect them. So, when you eat, the brain receives signals from both the smell receptors in your nose and the receptors in your tongue.

Scientists suspect that differences in the sense of smell—not taste—explain why people disagree over cilantro.

In Our Genes?

In 2012, researchers based at 23andMe, a company that sequences people’s DNA, looked for a genetic explanation. They asked their customers two simple questions: “Does fresh cilantro taste like soap to you?” and “Do you like the taste of fresh (not dried) cilantro?” Of the 14,604 people whose data they included, 1,994 said cilantro tasted like soap to them. The researchers then examined each person’s genome, the full set of their DNA, for small differences. In people who reported a soapy flavor, the researchers found a single change in their DNA: a difference in one nucleotide.

While this study did not turn up a single gene responsible for our ability to smell cilantro, it did uncover evidence that genetic differences may affect how people perceive it. The researchers identified a change within a stretch of DNA that contains instructions for eight olfactory (smell) receptors. They identified one of these receptors, called OR6A2, as the most likely source of the difference in perception.

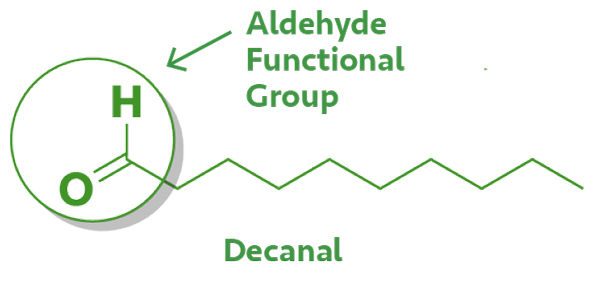

This receptor responds to aldehydes. Soaps are often scented using aldehydes and esters. The perception of buggy flavors also has a potential explanation: Insects, like plants, produce aldehydes. This may lead some people to associate the natural aldehydes in cilantro with the scent and flavor of soaps and insects.

Scientists still have a long way to go to solve the mystery of cilantro haters, however. The researchers calculated that the change they discovered accounts for only a very small portion of the difference in how people respond to cilantro. Given the complexity of the sense of smell, it’s possible that other genetic changes also contribute to how we perceive cilantro—at least to the portion we inherit, rather than learn.

Beyond Cilantro

Cilantro isn’t unique; genetic differences in both smell and taste influence how we perceive many other foods as well.

Scientists have linked changes to a taste receptor called TAS2R38, one of the sensors on your tongue’s taste buds, to differences in how people perceive bitterness. Vegetables such as broccoli, collard greens and cabbage contain bitter-tasting compounds that TAS2R38 detects, making them unpleasant to people who have a sensitive version of this gene.

Scientists have also linked genetic differences to how intensely we perceive the taste of monosodium glutamate (MSG, a chemical with a meaty, savory flavor) and even the sweetness from sugar and artificial sweeteners. New research has identified a change in an olfactory receptor that appears to make people like onions (and, as a result, likely to eat more of them).

Is there anything that tastes different to you than to other people? What do you think is responsible? It’s open for discussion.

Eriksson, N., Wu, S., Do, C. B., Kiefer, A. K., Tung, J. Y., Mountain, J. L., Hinds, D. A., & Francke, U. (2012, November 29). A genetic variant near olfactory receptor genes influences cilantro preference - flavour. BioMed Central. https://flavourjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2044-7248-1-22