Open for Discussion: The Asteroid Next Door

By Michael Tinnesand October 2019

We live in a world of finite metals.

What happens if we run out?

When it comes to commercial metals that make our cellphones and other devices function, the world is facing impending shortages that worry governments and businesses around the world. Demand for these strategic metals, such as gold, lithium, or rare-earth metals (those that are too dispersed to be mined in an economically feasible way), strains supplies. Political instability in countries where the metals are mined, in addition to trade tensions, further complicate the issue.

If we run out, there’s no rushing next door—say, to the moon—to borrow more. Or is there?

The idea isn’t as far-fetched as it might sound. The asteroid belt and the moon are brimming with metals. Dozens of spacecraft have already landed on the moon and Mars. Apollo missions brought back 382 kilograms (kg) of rock from the moon. In 2005, a spacecraft from Japan landed on an asteroid, collected samples, and brought them to Earth.

Big costs—bigger payoff?

To be clear, space mining would require overcoming major technological obstacles. But the challenges haven’t deterred ambitious entrepreneurs from forming dozens of private companies to set up mining operations in space.

While such ventures would be extremely costly and high risk (some have already gone under), the pay-off could be worth it. According to NASA estimates, the industry could generate revenues of $700 quintillion. That’s about 100 million times more than the total annual revenue of global mining in 2017, which was $600 billion.

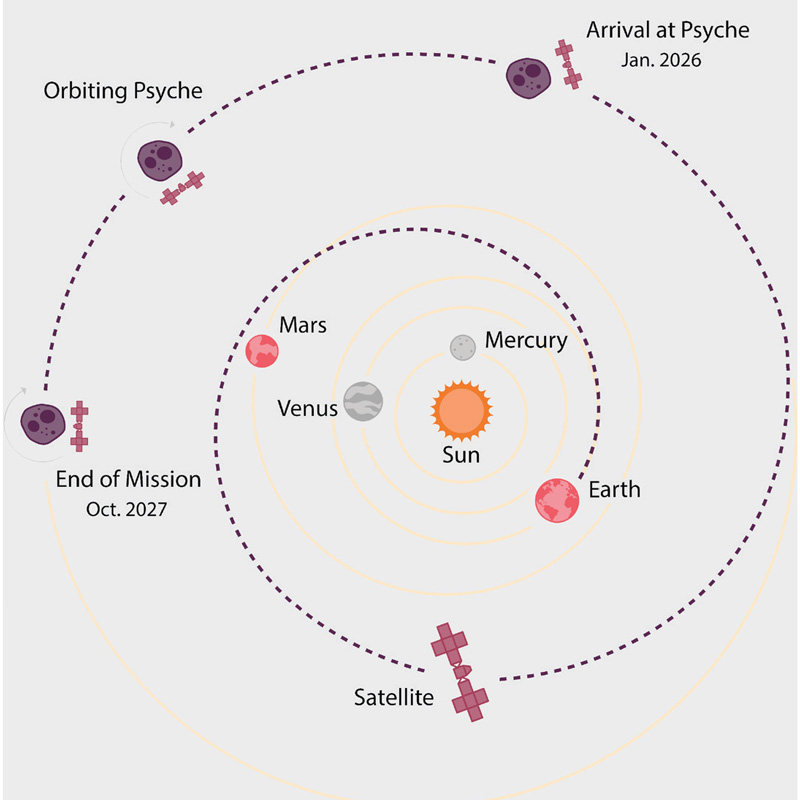

This asteroid called 16 Psyche is set to receive an earthly visitor. NASA approved a mission to send a spacecraft to the metallic rock in 2022 to study its composition. Scientists know Psyche is mostly made of iron and nickel, but they speculate it might also contain other metals such as gold.

But only the most valuable materials would likely be ferried to Earth. For example, rhodium, gold, and platinum, which sell for $70,000/kg, $45,000/kg, and $27,000/kg, respectively, could be among the metals worth transporting to Earth.

The rest of the material mined in space would likely remain there. Bringing back certain resources to Earth would be prohibitively expensive. Instead, the mining operations would largely be used to produce material for extraterrestrial exploration and for building colonies, such as those envisioned by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos.

“The reason we’ve got to go to space, in my view, is to save the Earth,” Bezos told reporters at a press conference in May announcing plans for his space company, Blue Origin, to build a moon lander.

Solving side effects

Mining in space could provide solutions for the continued production of advanced technologies well into the future, and for fulfilling dreams of traveling to and living in space. But one could argue that bringing back large quantities of valuable resources might be disruptive to current markets. Gold and other precious metals are of high value because of their scarcity. If they become abundant, prices could plummet. Oil, a once-limited resource, became abundant with exploration. Fossil fuels have enabled development and increased living standards, while also producing pollution and contributing to global climate change. Would cheap gold cause unintended side effects?

Additionally, where some entrepreneurs, scientists, and governments see asteroid mining as a solution to our earthly resource limitations, others are calling for caution: The accessible resources in the solar system would also one day run out. And then what?

What are our other options? That is still open for discussion.

Also in this Issue...

Interview with Brandon Jones

Lead Chemist, D.C. Department of Forensic Sciences

"If we find something new such as an unknown drug, trying to figure out what it is is a lot of fun—it’s usually a little bit of a mystery to unravel."