Sohio Acrylonitrile Process

Dedicated September 13, 1996, at BP Chemicals Inc. in Warrensville Heights, Ohio, and November 14, 2007, at INEOS in League City, Texas.

Commemorative Booklet: BP Chemicals Inc. 1996 (PDF)

Commemorative Booklet: INEOS, 2007 (PDF)

You may not know it by name, but acrylonitrile touches nearly everyone in some way every day. Acrylonitrile is the key ingredient in acrylic fibers used to make clothing, in plastics used to make computer, automobile and food casings, and in sports equipment. The material used in these and many other products was made by a process discovered and developed in the 1950s by scientists and engineers at Standard Oil of Ohio (Sohio), which later became part of the oil producing company BP. The nitrile business of BP was sold to INEOS in 2005.

Contents

Brief History of Acrylonitrile

The discovery and commercialization of the Sohio acrylonitrile process were the result of the talent, imagination, teamwork and risk-taking by Sohio's employees. Sohio's discovery led to the production of plentiful and inexpensive acrylonitrile of high purity as a raw material and to dramatic growth in the thermoplastics, synthetic fiber and food packaging industries.

Acrylonitrile, first synthesized in 1893 by Charles Moureu, did not become important until the 1930s, when industry began using it in new applications such as acrylic fibers for textiles and synthetic rubber. Although by the late 1940s the utility of acrylonitrile was unquestioned, existing manufacturing methods were expensive, multistep processes. They seemed reserved for the world's largest and wealthiest principal manufacturers: American Cyanamid, Union Carbide, DuPont and Monsanto. At such high production costs, acrylonitrile could well have remained little more than an interesting, low-volume specialty chemical with limited applications.

In the late 1950s, however, Sohio's research into selective catalytic oxidation led to a breakthrough in acrylonitrile manufacture. The people who invented, developed and commercialized the process showed as much skill in marketing as in chemistry. The result was such a dramatic lowering of process costs that all other methods of producing acrylonitrile, predominantly through acetylene, soon became obsolete.

Discovery of the Sohio Process

Founded by John D. Rockefeller, Sohio was a petroleum company known for efficient refining and skilled marketing. Before 1953, it had done no research on chemicals or petrochemicals; research was limited to the development of petroleum products and processes. No one among the 80 researchers working at Sohio's laboratory, then located on Cornell Road in Cleveland, was thinking about a shortcut to world-class acrylonitrile production.

The picture changed when Franklin Veatch, a research supervisor reporting to E.C. Hughes, Sohio’s director of research, proposed that converting light refinery gases such as the aliphatic hydrocarbon propane to oxygenates compounds containing oxygen; could be profitable. At the time, oxidation of aliphatic hydrocarbons was primitive and expensive. Veatch's idea was to use metal oxides to convert hydrocarbons to oxygenates. Funding was approved for this effort beginning in 1953.

In addition to starting new research, Sohio ventured into the petrochemical business by building ammonia and nitrogen plants in Lima, Ohio, and near Joplin, Missouri, to use by-products from its petroleum refinery. It was a conservative move, but it encouraged Sohio to view chemicals as a commercial enterprise; a venture that would lead to remarkable success.

Early experiments in Veatch's research yielded no major developments, and he was given a six-week deadline. The resulting crash program succeeded when a test run was made on propylene over a modified vanadium pentoxide oxidant, and the resultant odor was instantly recognizable as acrolein. Veatch knew that one more oxidation step would take acrolein to acrylic acid—an important, expensive, fast-growing monomer. For the next two years, several researchers, including Ernest C. Milberger, James L. Callahan, Robert W. Foreman, James D. Idol, Jr., Evelyn Jonak and Emily A. Ross, were involved in this development effort.

In 1955 the team began testing oxidants as direct oxidation catalysts. In an experiment designed by Jim Callahan and performed by Emily Ross, bismuth phosphomolybdate produced acrolein in yields of 40 percent or more. This was a first-magnitude discovery: propylene to acrolein in a single catalytic reaction step. Acrylic acid could be made in a subsequent step. Callahan, Foreman and Veatch secured key patents on the bismuth phosphomolybdate catalyst, and from then on, things were destined to happen fast.

Jim Idol suggested acrylonitrile as a derivative of acrylic acid and successfully carried out catalytic conversion of the ammonium salt of acrylic acid. Next, acrylonitrile was made by feeding acrolein, ammonia and air over the catalyst that produced acrylic acid from acrolein. This success suggested that acrylonitrile might be made directly from propylene by carrying out the entire reaction in a single step with bismuth phosphomolybdate. The experiment, designed by Idol and performed by Evelyn Jonak in March, 1957, resulted in ammoxidation, a process that produced acrylonitrile in about 50 percent yield with acetonitrile and hydrogen cyanide as co-products.

With the capacity to make acrolein, acrylic acid and acrylonitrile by efficient, revolutionary new processes, Veatch pressed for a strong development and commercialization effort. The Patents and Licensing Department went to work on securing an iron-clad patent position. Because manufacturing both acrylic acid and acrylonitrile proved to be too ambitious, acrylonitrile production became the priority.

Sohio Gambles with Acrylonitrile Production

Sohio's process economics for acrylonitrile were so positive that the decision was made to proceed with commercialization even though early market development efforts were discouraging. Major users were unsure that Sohio acrylonitrile would satisfy their needs. One major chemical company declined an opportunity for a joint venture. Another company announced plans for a new 100-million-pound-per-year acrylonitrile plant based on the old acetylene technology, at a cost of $100 million.

Still, Sohio commissioned the design of a detailed acrylonitrile plant. A pilot plant was constructed under the direction of Gordon G. Cross at Sohio's new laboratory in Warrensville Heights, a Cleveland suburb, where Ernie Milberger was instrumental in designing large laboratory-scale reactors and obtaining process design and development data from them.

In a bold move, it was decided to design the commercial plant on the basis of bench-scale laboratory development data rather than wait for pilot plant results. The time gained by eliminating this stage of development offset the added risk. Milberger's bench-scale unit, which required about four pounds of catalyst, generated the key data for the design of commercial reactors holding 40 tons.

By early 1958, the commercial design was going forward under the direction of Edward F. Morrill; a pilot plant was in operation; the catalyst was in final development by Callahan and his team with provisions for large-scale manufacture; and advancement work on reactor operation, product purification, and waste disposal was being coordinated. A key innovation was the successful development of a fluidized bed catalyst to allow for removal of the heat produced by the ammoxidation reaction.

By mid-winter 1959-60, the Lima, Ohio, plant, which cost $10 million to build, was complete. In less than four years since the discovery of bismuth phosphomolybdate as the direct propylene oxidation catalyst and the discovery of propylene ammoxidation, a full-scale commercial plant designed to produce 47.5 million pounds of acrylonitrile per year was ready to go.

There was but one challenge left—an economic one. Soon after Sohio's entry, a major manufacturer cut its price in half. Sohio met the lower price and still managed to make a profit. The competitor scrapped its own expansion plans and took a license from Sohio. Other acrylonitrile producers soon became licensees of the Sohio process, and within a few years, acetylene-based acrylonitrile production had been replaced by the Sohio process.

To gain a larger share of the overall market, Sohio decided to promote the licensing of the process rather than keep the manufacturing to itself. Sohio's license to The People's Republic of China in 1973 was the first transaction by an American company after China opened its doors to U.S. investment. Today the Sohio Acrylonitrile Process is utililzed in over 90% of the world’s acrylonitrile production, representing plants in sixteen countries worldwide. Annual worldwide production of acrylonitrile has grown from 260 million pounds in 1960 to more than 11.4 billion pounds in 2005.

Since 1960 several improved catalyst formulations have been developed, most of them based on the original bismuth phosphomolybdate catalyst. INEOS's current research focuses on further improvements to the Sohio Acrylonitrile Process.

The People Behind the Sohio Process

Six individuals played the most prominent roles in Sohio's acrylonitrile project.

Franklin Veatch was research supervisor for petro-chemicals, polymers, and new petroleum processes. He possessed a technical, creative genius, and he inspired co-workers to achieve a goal, however impossible it might seem. Veatch received his B.S. and M.S. degrees from the University of Arizona and his Ph.D. from Stanford University in 1947. He held 61 U.S. patents by the time of his retirement in 1978. He died in 1980.

James L. Callahan, a research associate, coordinated catalyst research and development, including the discovery of improved methods of catalyst manufacture. He was renowned for converting hydrocarbon materials to petrochemicals. Callahan received his B.S. degree from Baldwin-Wallace College and his M.S. degree and, in 1957, his Ph.D. from Case Western Reserve University. Retired since 1985, he is credited with more than 200 patents and publications.

Edward F. Morrill, as president of Vistron Corp., was the product-process champion on the business side. Vistron was the chemical division of Sohio from 1966 to 1982. Morrill received his bachelor's degree in civil engineering from Case Institute of Technology in 1929. His ability to “see” a revolutionary and economically dominating chemical process was crucial to the project's success. Morrill took the necessary risks that led to successful commercialization.

James D. Idol, Jr., a research associate who supervised and carried out research and feasibility testing, holds the basic patent for the process. He received his B.A. degree in chemistry from William Jewell College and, in 1955, his Ph.D. in chemistry from Purdue University.

Ernest C. Milberger, a research associate, carried out the advancement of the Sohio process from small-scale research to pilot plant. He received his A.B. and M.A. degrees in chemistry from the University of Missouri and his Ph.D. from Case Western Reserve University in 1957. He holds 80 patents, mostly in the catalytic process area.

Gordon G. Cross, a development supervisor, was responsible for pilot plant development of the Sohio process, as well as for preliminary engineering and precommercial economic evaluation of the overall process concept. He received his B.S. degree in chemical engineering from Ohio State University and, in 1960, his M.S. degree in engineering administration from Case Institute of Technology.

Other significant contributors to the invention, development, and commercialization of the Sohio process include Arthur F. Miller a research associate who developed the commercial method for manufacturing improved catalysts; Robert K. Grasselli, a catalyst research associate who was involved in the early oxidation research, the development of subsequent generations of Sohio catalysts, and the detailed mechanisms of ammoxidation reactions; and Robert W. Foreman, a group leader during the early research phase and a co-inventor of the bismuth phosphomolybdate propylene-to-acrolein catalyst.

Landmark Designation and Acknowledgments

Landmark Designation

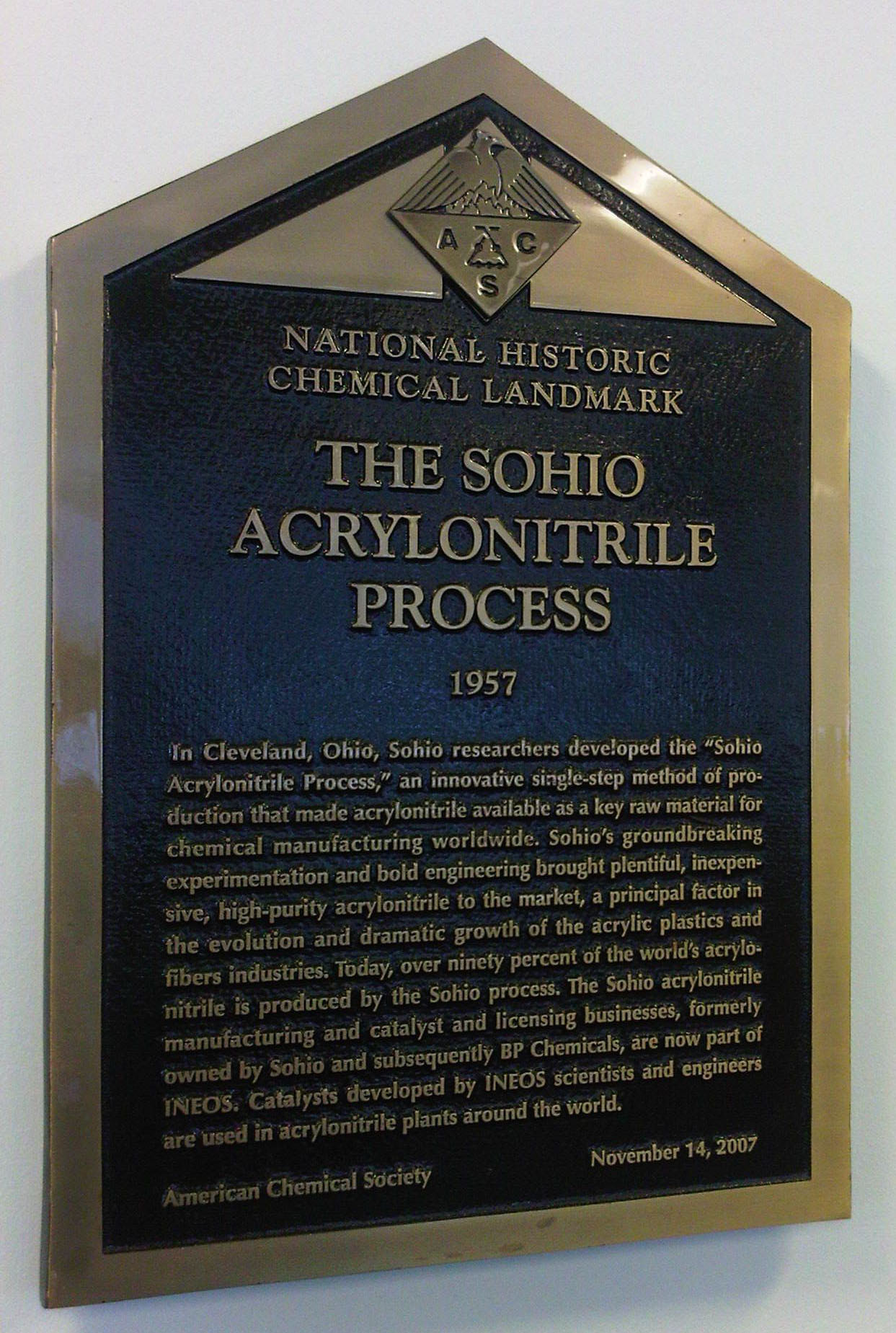

The American Chemical Society designated “The Sohio Acrylonitrile Process” a National Historic Chemical Landmark at BP Chemicals Inc. in Warrensville Heights, Ohio, on September 13, 1996, and at INEOS in League City, Texas, on November 14, 2007.

The text of the commemorative plaque presented to BP Chemicals, Inc., reads:

At this site, Sohio researchers developed the “Sohio Acrylonitrile Process,” an innovative single-step method of production that made acrylonitrile available as a key raw material for chemical manufacturing worldwide. Sohio’s groundbreaking experimentation and bold engineering brought plentiful, inexpensive, high-purity acrylonitrile to the market, a principal factor in the evolution and dramatic growth of the acrylic plastics and fibers industries. Today, nearly all acrylonitrile is produced by the Sohio process, and catalysts developed at the Warrensville Laboratory are used in acrylonitrile plants around the world. Sohio became part of The British Petroleum Company p.l.c. in 1987.

The text of the commemorative plaque presented to INEOS reads:

In Cleveland, Ohio, Sohio researchers developed the “Sohio Acrylonitrile Process,” an innovative single-step method of production that made acrylonitrile available as a key raw material for chemical manufacturing worldwide. Sohio’s groundbreaking experimentation and bold engineering brought plentiful, inexpensive, high-purity acrylonitrile to the market, a principal factor in the evolution and dramatic growth of the acrylic plastics and fibers industries. Today, over ninety percent of the world’s acrylonitrile is produced by the Sohio process. The Sohio acrylonitrile manufacturing and catalyst and licensing businesses, formerly owned by Sohio and subsequently BP Chemicals, are now part of INEOS. Catalysts developed by INEOS scientists and engineers are used in acrylonitrile plants around the world.

Acknowledgments

Adapted for the internet from “The Sohio Acrylonitrile Process,” produced by the National Historic Chemical Landmarks program of the American Chemical Society in 2007.

Back to National Historic Chemical Landmarks Main Page.

Learn more: About the Landmarks Program.

Take action: Nominate a Landmark and Contact the NHCL Coordinator.