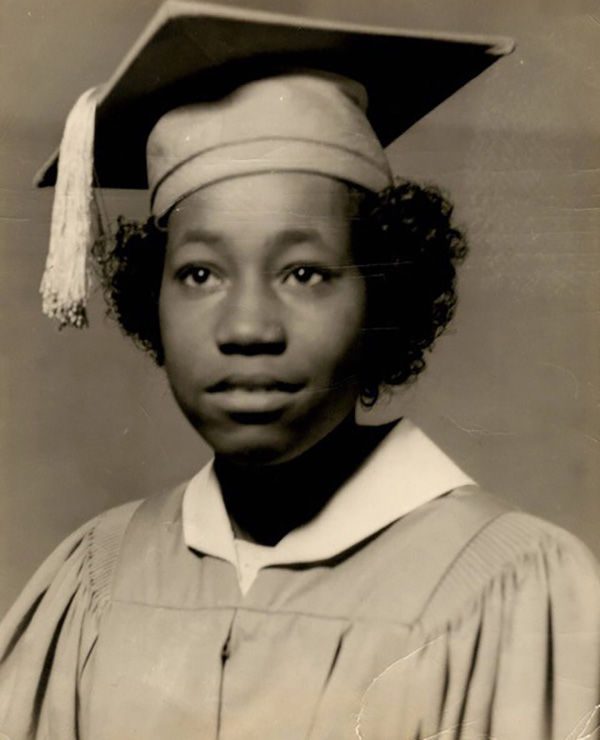

Bettye Washington Greene, Ph.D.

Dedicated at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, on October 27, 2023

Bettye Washington Greene grew up in an environment that was in many ways hostile, rigid, and determined to keep her from succeeding. But as one of the first female Black commercial chemists in the U.S., Washington Greene didn’t let the racism, sexism, and classism of the 20th century hinder her. She overcame these roadblocks to make significant contributions to the field of materials science.

Contents

A challenging environment

Born in 1935 in Palestine, Texas, Washington Greene (née Washington) was surrounded by a racist ideology that permeated much of the U.S. Although slavery had been abolished in the state in the 1860s, segregation and civil rights infringements continued. In fact, informal systems of oppression were being codified. In 1925, for example, the Texas state legislature mandated all schools be racially segregated, deemed it illegal for any public area to be integrated, and decreed interracial relationships a felony.

Fortunately for Washington Greene, by the time she was a teen in the 1940s and 1950s, the segregated I. M. Terrell High School in Fort Worth, Texas, had become part of a program called the Black High School Study. The program invited Black teachers to help develop a new curriculum known as progressive education. The program was hands-on and experience-based, and it approached learning via problem solving. It also incorporated community and social projects.

For Washington Greene, it was a recipe for success.

She excelled at school and was especially drawn to science. With the end of World War II, scientific discoveries that had been developed for the war effort were yielding a windfall for the country. Corporations that had assisted in weapons production, like DuPont and Monsanto, pivoted to doing business with the private sector. Public interest in space was taking hold, vaccines were being developed to save lives, and young people were becoming enamored with chemistry sets at home. But those chemistry sets were often labeled “for boys,” and very few women pursued studies in scientific fields.

That didn’t matter to one of Washington Greene’s high school teachers, who saw the budding student’s talents and encouraged her to explore chemistry.

When Washington Greene graduated from high school in the early 1950s, there were few professional pathways available for Black women — or for women in general. Mostly, young women were funneled into nursing or teaching careers. Washington Greene wasn’t interested in either career. She moved to Alabama to attend the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), a co-educational, historically Black college.

By the time Washington Greene graduated with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1955, the civil rights era had officially begun. The Supreme Court had ended discriminatory “separate but equal” laws and outlawed school segregation in its Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

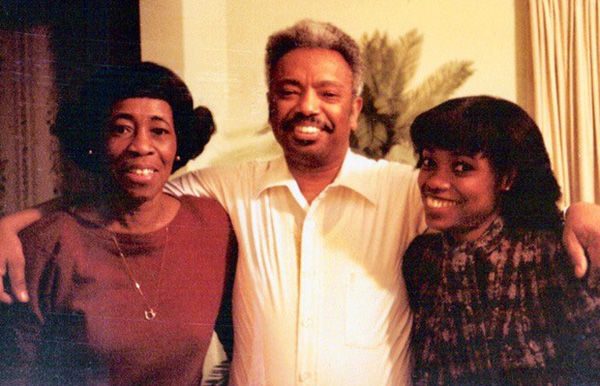

At Tuskegee, she met William Greene, an engineer who trained Tuskegee Airmen. They married two months after graduation, and over the next several years had two daughters and a son. In the years following her undergraduate studies, Washington Greene took care of the household and the children, but she never lost her love of chemistry.

[Bettye Washington Greene], who earned her Ph.D. in chemistry from Wayne State in 1965, is the fifth African American woman awarded a doctoral degree in chemistry and the first to be hired in the chemical industry.”

— Sibrina Collins, American Association for the Advancement of Science-Improving Undergraduate STEM Education Initiative blog, 2023

Graduate school beckons

By the early 1960s, Washington Greene decided that she wanted to continue her education. She applied to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Wayne State University in Detroit for graduate school. She was accepted into both programs, but she chose Wayne State because its offer included a grant from the Office of Naval Research. Washington Greene’s mother offered crucial support by taking care of her children in Texas while Washington Green attended her graduate program. William Greene moved with his wife and took a job as an engineer for the Chrysler Corporation.

Her graduate advisor at Wayne State was Wilfried Heller, who Washington Greene said provided “patience, understanding, and invaluable guidance” during her laboratory work. With his supervision, Washington Greene dove into the field of physical chemistry, specifically the properties of particles.

Particle size significance

It was known that the size of the particles that make up a liquid, solid, or gas has a substantial effect on how that matter behaves. And Washington Greene knew that it was important to be able to quantify particle sizes to figure out how best to use them in material applications.

That particle size is important was known by the ancient Egyptians, who used sieves in the processing of ores beginning around 4000 B.C. In 1850, Irish physicist George Gabriel Stokes reported a way to measure viscosity — how much a fluid resists flow — by measuring particles falling in a viscous suspension. In 1906, Albert Einstein published his findings on how particle size in fluids affects viscosity.

Scientists soon realized the importance of particle size in a variety of industries, as diverse as the pharmaceutical sector and construction. These applications prompted many questions: What size particles are dangerous to inhale? What size particles can be absorbed from a pill into the bloodstream? What size particles should be used in toothpaste to polish teeth but not scratch them? What size particles of powder can be melted into iron to make the metal stronger?

Washington Greene advanced the sciences dealing with particle size with an innovative method that used beams of light. To determine particle sizes in a solution, she measured how much light passed straight through the liquid and how much light was scattered by particles in different directions. With that data, she could calculate the diameter of particles present in the liquid.

Washington Greene finished graduate school in 1965 and defended her doctoral thesis, entitled “Determination of Particle Size Distributions in Emulsions by Light Scattering.” She was the fifth Black woman to earn a doctorate in chemistry in the U.S.

[Dr. Washington Greene’s] legacy continues through the valuable citations of her research, her impact on the materials science and chemistry communities, and her status as a role model for the many who have and will follow after her example.”

— Clinique Brundidge and Valentino Cooper, The Journal of The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society, 2022

A first in industry

Later that year, Washington Greene was recruited by The Dow Chemical Company in Midland, Michigan. She was the first Black female research scientist on the company’s staff. In fact, she was the first Black American female Ph.D. chemist hired by any chemical company.

According to her daughter Willetta Greene Johnson, the company had admirable family values. “They hired Mom, but said, ‘Well, your husband needs a job as well, so the family can be together, stay intact,’ Greene Johnson said. “They actually scoured the rest of the company in Midland to see if they could find a job for Dad. Finally, they said, ‘We’re in the chemical business and don’t have a lot of need for electrical engineers. But we just bought this new thing from IBM — a computer — do you think you could tinker with that?’” Greene became the top computer expert — so much so that he had to carry a pager at all times, even to church.

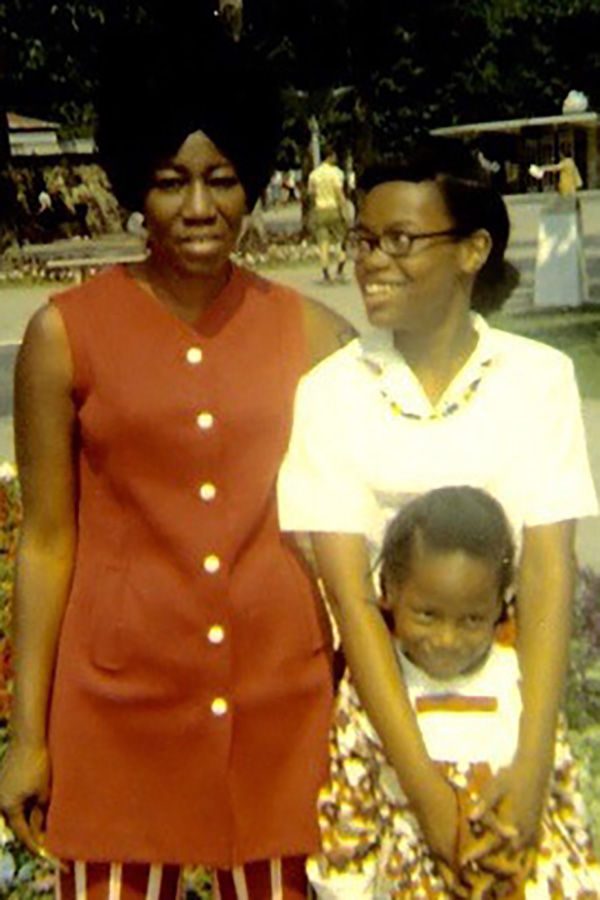

Washington Greene and her husband raised their children with a solid foundation in science. She commonly threw chemical terms into the family’s daily routines. Instead of saying milk had spoiled, she’d say it had coagulated, recalled one of her daughters in a 2022 interview. “She would talk about viscosity even as we were cooking,” said Greene Johnson, “and that was [not only an] atypical African American experience. It was an atypical American experience.”

But it wasn’t all science all the time, said Greene Johnson. “Although we heard a lot of science terms growing up, my parents greatly enjoyed music too. My mother would listen to artists like Ella Fitzgerald and Barbara Streisand, and my dad was fond of bands such as The Beatles and Earth, Wind & Fire.” Their musical tastes dated all the way back to Beethoven.

Greene Johnson developed a passion for both music and science, and later went on to become a physics professor at Loyola University Chicago, as well as an accomplished songwriter and composer, winning a Grammy award in 2004.

Flush times at Dow

The 1960s were a boom time for Dow. New manufacturing plants and research facilities were popping up around the world. The giant corporation began to commercialize its household products with gusto — from food storage Saran Wrap® to cleaning product Scrubbing Bubbles®, Dow products were in many homes. And when Neil Armstrong became the first person to step on the moon, in 1969, the boot he planted on the lunar surface had a rubber silicone sole, compliments of Dow scientists.

For Washington Greene, Dow’s Saran Research Laboratory was a place to expand on her love of materials science. Her first order of business was to study the firm’s synthetic latex, which consists of polymer particles suspended in water. In 1970, because of her groundbreaking light scattering techniques, Washington Greene received a promotion to senior research scientist. Three years later, she joined the Designed Polymers Research Division, where her work contributed to innovations in pharmaceuticals, coatings, cosmetics, paints, and catalysts.

Washington Greene was issued three patents, including “Stable latexes containing phosphorus surface groups,” which describes the use of polymers to create durable coatings on paper. Now nearly 50 years later, her work continues to be cited in professional science journals.

Despite her success, Washington Greene felt the sting of inequality. “She went up the ranks,” said her daughter Greene Johnson in a 2021 interview, “but she was frustrated towards the end of her career.” Greene Johnson added that her mother was training other employees with lesser credentials who were being promoted above her. “She told me that it was challenging to climb the ladder as a woman, [particularly] as a woman of color.”

Washington Greene retired from Dow in 1990. She passed away on June 16, 1995, at the age of 60.

To honor the late chemist, Wayne State University launched the Bettye Washington Greene Endowed Memorial Lecture Series in 2022. The series of lectures initiated by Wayne State Professor of Chemistry Christine Chow exposes first-generation college students and students of color to science careers in industry.

Washington Greene’s tenure at Dow opened the doors for other researchers of color, said Dow chemist Vannesa Jansma in a 2022 video interview. “Being able to be patented, a published scientist and then [to have] your work being used for further processing [downstream]… I think that’s huge.”

Landmark dedication and acknowledgments

Landmark dedication

The American Chemical Society (ACS) honored Bettye Washington Greene with the National Historic Chemical Landmark (NHCL) designation in a ceremony at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, on Oct. 27, 2023. The commemorative plaque reads:

Bettye Washington Greene was a pioneer. When she began her career as a research scientist at The Dow Chemical Company in Midland, Michigan, she became the first female Black American Ph.D. chemist hired in the chemical industry. She was also the fifth Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry in the U.S. Her doctorate was awarded by Wayne State University in 1965. Washington Greene’s research on light scattering techniques, latexes, and other subjects contributed to innovations in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, paints, coatings, and catalysts. In the course of this work, she was issued three patents. Washington Greene died on June 16, 1995, at the age of 60.

Acknowledgments

Written by Victoria Bruce.

The author wishes to thank contributors to and reviewers of this booklet, all of whom helped improve its content, especially members of the ACS NHCL Subcommittee.

The nomination for this Landmark designation was prepared by the Detroit Local Section and the Midland Section of the ACS.

Related Landmarks

ACS has recognized a number of Black chemists with the Landmark designation. They include Marie Maynard Daly, the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry in the U.S., and St. Elmo Brady, the first Black man to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry in the U.S.