Rachel Lloyd, Ph.D., Pioneering Woman in Chemistry

National Historic Chemical Landmark

Designated October 1, 2014, at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Rachel Holloway Lloyd was a pioneer in the field of chemistry. Lloyd became the first American woman to earn a doctoral degree in chemistry when she graduated from the University of Zurich in 1887. Six years earlier, she had become the first woman to publish research in a major American chemical journal. And when Lloyd joined the faculty of the University of Nebraska, she was among the earliest women to teach and conduct research at a coeducational university. In a life of near-constant adversities, Lloyd achieved distinction for her teaching and research and earned wide admiration by her colleagues and students.

Rachel Lloyd's Early Life

Rachel Abbie Holloway was born on January 26, 1839, to Robert Smith Holloway and Abigail Taber, a Quaker couple in Smyrna (or Flushing), Ohio. The family faced a series of tragedies. Of their four children, only Rachel survived past infancy. When she was five years old, Rachel’s mother died, and seven years later, her father died as well. From age 12, Rachel was raised by her stepmother from her father’s second marriage.

At the age of 14, Rachel was sent to boarding school near Philadelphia, and she began teaching at a girls finishing school upon her graduation. In 1859, Rachel married Franklin Lloyd, an employee of Powers & Weightman, a large chemical producer in the city. Franklin graduated from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy in 1861 and worked as a chemist and businessman.

Rachel later said that Franklin kept a chemical laboratory in their home, and her introduction to the field came through her husband’s work. The Chicago Daily Tribune interviewed Lloyd in 1893 and wrote,

“The girl-wife dearly loved to perch herself, with some bit of sewing, in the deep window of her husband’s laboratory, which was a part of their home, and, as she became familiar with the apparatus and watched the experiments with wondering eyes, she little dreamed that the same work would one day be hers in even more extended fields.”

In 1863, the Lloyds moved to Michigan, where Franklin pursued new business interests. Two years later, he died. The couple’s two infant children preceded him in death. Rachel, a widow at age 26, took her sizeable estate and traveled for several years in Europe. A financial panic 10 years later left her without the means to support herself abroad, and she returned to the U.S. to find work.

Lloyd's Early Teaching and Training

Upon her return, Lloyd taught chemistry at the Chestnut Street Female Seminary, a prominent girls finishing school in Philadelphia. For women teachers at the time, positions in primary schools and girls finishing schools were among the highest they could hope to attain. Lloyd was noted for introducing laboratory experiments into the curriculum at Chestnut Street—a rarity in science courses for women and girls of any age in this era.

Lloyd applied her knowledge of chemistry from her husband’s profession, but she also worked to attain an education for herself. In 1875, she enrolled in summer school at Harvard University, where she learned to do chemical research. Harvard, like most leading universities at the time, did not accept women as regular students. The summer school offered teachers training, although without the chance to earn a degree. Lloyd took seven chemistry courses and audited several botany courses in the summers from 1875 until 1883.

While at Harvard, Lloyd studied advanced quantitative chemistry under Charles F. Mabery (1850–1927), director of the summer chemistry program. In 1881, Mabery and Lloyd published their research in the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Chemical Journal, marking the first publication by a woman author in a major chemical journal in the U.S. Two subsequent publications by Mabery and Lloyd followed in 1882 and 1884.

Lloyd taught briefly at a girls school in New York before becoming an instructor of chemistry and physics at the Hampton College for Women in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1882. Two years later, she added the position of chemistry instructor at the Louisville School of Pharmacy for Women.

In 1884, Lloyd applied for a position as professor of chemistry at the newly-established Bryn Mawr College, a women’s college outside of Philadelphia. Despite her years of teaching experience and a favorable reference by Mabery, Lloyd’s application was declined. The college cited her lack of degree in its explanation. Lloyd, whose ambition was to teach at the collegiate level, resolved to earn a degree.

Women in the Sciences in the 1800s

While a handful of universities in the U.S. accepted women into doctoral programs at the time—Boston University awarded Helen Magill a Ph.D. in classics in 1877, the first doctoral degree granted to a woman in the U.S.—none had accepted a female candidate in chemistry. For the sciences and mathematics, the University of Zurich, in Switzerland, was the leading center for women’s higher education. In admitting women, Zurich was a rare exception among the prestigious German-speaking universities.

At Zurich, Lloyd studied under the organic chemist August Viktor Merz (1839–1904). She stood among a small group of women studying advanced chemistry in the late 1800s. The Russian Julia Lermontova (1846–1919) had earned her doctorate in chemistry in 1874 from the University of Göttingen, becoming the first woman to receive the degree. A notable American example, Ellen Swallow Richards (1842–1911), earned bachelor degrees in chemistry from Vassar College (1870) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1873). Richards hoped to receive a doctorate at MIT, but the university did not accept women into its graduate programs at the time.

Other fields provided more opportunities for women than chemistry. A handful of women had been earning medical degrees in Europe and the U.S. since the 1860s. In the 1880s, women made great strides in botany. The physical sciences, however, remained the domain of men, and women were at times strongly discouraged from entering. Rachel Bodley (1831–1888), a founding member of the American Chemical Society, resigned from the association following a meeting at which womankind itself was the object of criticism. Such misogynistic sentiments in the sciences reflected broader tensions surrounding women’s roles in society at a time when few entered the workforce and women lacked the right to vote in most states.

On February 21, 1887, at age 48, Lloyd graduated from the University of Zurich with the thesis, “On the conversion of some of the homologues of benzol-phenol into primary and secondary amines.” She was the first American woman (and second woman in the world) to receive a doctoral degree in chemistry.

Dr. Lloyd was a woman of unusual ability. By means of thorough scientific training and hard work she attained for herself a place in the scientific world above that ordinarily reached by a woman.”

—Rosa Bouton, R. Lloyd memorial address, 1900

Rachel Lloyd at the University of Nebraska

Shortly after her graduation from Zurich, Lloyd received a letter from Henry Hudson Nicholson (1850–1940), chair of the Chemistry Department at the University of Nebraska, asking her to join the faculty there. Lloyd and Nicholson had met during their Harvard summers, both having studied under Mabery. Nicholson presented Lloyd with a rare opportunity to teach and conduct research at a co-educational university at a time when most of her female peers were relegated to teaching at secondary schools or women’s colleges.

Lloyd left London, where she briefly had worked as an assistant at the Normal School of Science and Royal School of Mines (now the Imperial College of London). She arrived in Lincoln, Nebraska, in the summer of 1887. The university, which had been chartered in 1869, was undergoing a major expansion and modernization around this time as it transitioned from a preparatory school to a full-fledged university. Lloyd was the second member of the chemistry faculty after Nicholson and the only one holding a doctoral degree. She arrived one year after the dedication of the university’s chemical laboratory building.

Upon her arrival, Lloyd was named associate professor of analytic chemistry. In addition to her teaching responsibilities, Lloyd took on the role of assistant chemist at the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station. Her research was supported by the federal Hatch Act of 1887, which provided funding for the founding of agricultural experiment stations across the country.

One year after she was hired, a tumultuous episode ensued wherein Lloyd was threatened with non-renewal of her contract. Newspapers reported that the university’s chancellor, James Irving Manatt (1845–1915), levied a personal attack against Lloyd, possibly driven by questions about her Quaker religion. A vote of confidence by the university’s faculty resulted in Lloyd’s reinstatement, and she was promoted to full professor. Amid growing unpopularity, Manatt stepped down shortly thereafter. From that year on, Lloyd received wide praise by faculty and students for her technical expertise, teaching ability, and devotion to public service. She became a popular figure at the university due in equal parts to her warm personality and her cultural refinement, provided by an Eastern upbringing and extensive European travels.

Lloyd’s research at Nebraska centered on chemical analyses of the concentration of sugars in sugar beets, an emerging crop in the U.S. in the late 1800s. Lloyd had been introduced to the sugar beet while studying in Switzerland. Her expertise and the new agricultural station in Lincoln provided an opportunity to explore the possibility of raising beets across Nebraska.

Lloyd and Nicholson grew a test crop of beets in 1888 and determined there was a favorable outlook for the crop. The following year, the team sent seeds to farmers across the state in an effort to conduct a wider study. At the end of the season, farmers returned their harvests to Lincoln, where they were washed and weighed. A sample from the core of the beet was pulped and pressed to release its juices. . Total sugar concentration was determined using a saccharometer, which works according to Archimedes’ principle of displacement, and a test called Fehling’s reduction. The survey noted each crops’ seed variety, soil profile, and climate, among other variables. Lloyd and a team of student researchers completed roughly 700 such analyses.

Nicholson and Lloyd published the first of three reports on sugar production in the state in 1890. Findings were so encouraging that investors established a sugar factory near Grand Island in the same year. It was the third successful commercial sugar beet refinery in the U.S. and the first in the Great Plains. Production in Nebraska expanded rapidly, from 736,000 pounds of granulated sugar in 1890 to 8,378,000 pounds in 1895, and additional factories were built. Shortly after, the university established a sugar school to train workers for the state’s growing sugar industry.

When Nicholson traveled in Europe during the spring and summer of 1892, Lloyd served as acting chair of the chemistry department. That summer, while traveling, she suffered an attack of partial paralysis, a condition from which she never fully recovered. Because of her health problems, Lloyd announced her retirement from the university in the spring of 1894.

Lloyd briefly took a position teaching science at the Hillside Home School in Spring Green, Wisconsin, but her poor health prohibited her from serving a second year. She returned to the Philadelphia area to live near friends and relations. On March 7, 1900, Lloyd died at the age of 61.

Lloyd’s research at Nebraska centered on chemical analyses of the concentration of sugars in sugar beets, an emerging crop in the U.S. in the late 1800s. Lloyd had been introduced to the sugar beet while studying in Switzerland. Her expertise and the new agricultural station in Lincoln provided an opportunity to explore the possibility of raising beets across Nebraska.

Lloyd and Nicholson grew a test crop of beets in 1888 and determined there was a favorable outlook for the crop. The following year, the team sent seeds to farmers across the state in an effort to conduct a wider study. At the end of the season, farmers returned their harvests to Lincoln, where they were washed and weighed. A sample from the core of the beet was pulped and pressed to release its juices. . Total sugar concentration was determined using a saccharometer, which works according to Archimedes’ principle of displacement, and a test called Fehling’s reduction. The survey noted each crops’ seed variety, soil profile, and climate, among other variables. Lloyd and a team of student researchers completed roughly 700 such analyses.

Nicholson and Lloyd published the first of three reports on sugar production in the state in 1890. Findings were so encouraging that investors established a sugar factory near Grand Island in the same year. It was the third successful commercial sugar beet refinery in the U.S. and the first in the Great Plains. Production in Nebraska expanded rapidly, from 736,000 pounds of granulated sugar in 1890 to 8,378,000 pounds in 1895, and additional factories were built. Shortly after, the university established a sugar school to train workers for the state’s growing sugar industry.

When Nicholson traveled in Europe during the spring and summer of 1892, Lloyd served as acting chair of the chemistry department. That summer, while traveling, she suffered an attack of partial paralysis, a condition from which she never fully recovered. Because of her health problems, Lloyd announced her retirement from the university in the spring of 1894.

Lloyd briefly took a position teaching science at the Hillside Home School in Spring Green, Wisconsin, but her poor health prohibited her from serving a second year. She returned to the Philadelphia area to live near friends and relations. On March 7, 1900, Lloyd died at the age of 61.

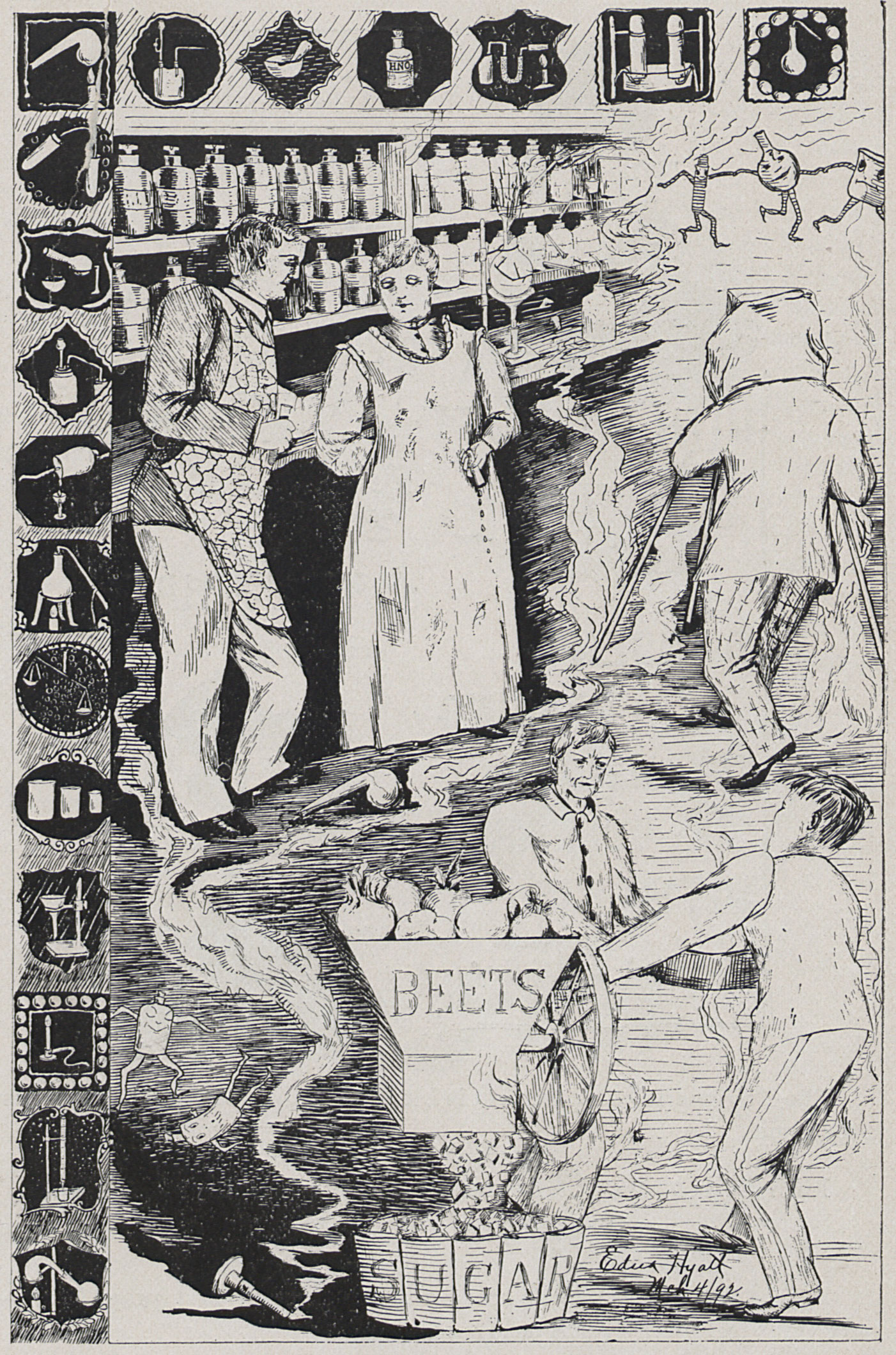

Lloyd's Research: Sugar Beets in Nebraska

Lloyd’s research at Nebraska centered on chemical analyses of the concentration of sugars in sugar beets, an emerging crop in the U.S. in the late 1800s. Lloyd had been introduced to the sugar beet while studying in Switzerland. Her expertise and the new agricultural station in Lincoln provided an opportunity to explore the possibility of raising beets across Nebraska.

Lloyd and Nicholson grew a test crop of beets in 1888 and determined there was a favorable outlook for the crop. The following year, the team sent seeds to farmers across the state in an effort to conduct a wider study. At the end of the season, farmers returned their harvests to Lincoln, where they were washed and weighed. A sample from the core of the beet was pulped and pressed to release its juices. . Total sugar concentration was determined using a saccharometer, which works according to Archimedes’ principle of displacement, and a test called Fehling’s reduction. The survey noted each crops’ seed variety, soil profile, and climate, among other variables. Lloyd and a team of student researchers completed roughly 700 such analyses.

Nicholson and Lloyd published the first of three reports on sugar production in the state in 1890. Findings were so encouraging that investors established a sugar factory near Grand Island in the same year. It was the third successful commercial sugar beet refinery in the U.S. and the first in the Great Plains. Production in Nebraska expanded rapidly, from 736,000 pounds of granulated sugar in 1890 to 8,378,000 pounds in 1895, and additional factories were built. Shortly after, the university established a sugar school to train workers for the state’s growing sugar industry.

When Nicholson traveled in Europe during the spring and summer of 1892, Lloyd served as acting chair of the chemistry department. That summer, while traveling, she suffered an attack of partial paralysis, a condition from which she never fully recovered. Because of her health problems, Lloyd announced her retirement from the university in the spring of 1894.

Lloyd briefly took a position teaching science at the Hillside Home School in Spring Green, Wisconsin, but her poor health prohibited her from serving a second year. She returned to the Philadelphia area to live near friends and relations. On March 7, 1900, Lloyd died at the age of 61.

Legacy of Rachel Lloyd

Lloyd’s time at the University of Nebraska launched a period for the campus as an important node for women’s education in chemistry that was unusual among its peers. Between 1888 and 1915, 10 of the 46 graduate students in the chemistry department were women. Eight of these joined the Nebraska Local Section of the American Chemical Society, which accepted more women members than any other during these years. The university’s first two women chemistry graduate students became faculty members in the chemistry department: Rosa Bouton (1860–1951, B.S. 1891, M.A. 1893) and Mary Fossler (1868–1952, B.S. 1894, A.M.1898). Bouton went on to found the university’s School of Domestic Science (now the Department of Nutrition & Health Sciences) in 1898.

Lloyd was involved in a number of scientific associations of local and national importance. In 1889, Lloyd was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In 1890 and 1891, Lloyd served on the Science Committee of the Association for the Advancement of Women, an organization that called for the expansion of opportunities for women in science, among other causes. Also in 1891, Lloyd was elected as a member of the American Chemical Society in a class that included Nicholson; she was the first woman admitted since Rachel Bodley’s departure.

Lloyd helped found a number of societies and clubs in Lincoln, including the Nebraska Academy of Sciences, the Nebraska Local Section of the American Chemical Society, and the Haydon Art Club of the University of Nebraska (predecessor to the Sheldon Museum of Art). The Sheldon Museum of Art now stands on the site of the university’s original chemistry building, in which Lloyd worked.

Further Reading

- Rachel Lloyd ACS National Historic Chemical Landmark (University of Nebraska–Lincoln)

- Rachel Lloyd: Early Nebraska Chemist (M.R.S. Creese and T.M. Creese, Bulletin for the History of Chemsitry, ACS Divsion of the History of Chemistry)

- Rachel Holloway Lloyd (Chemical Heritage Foundation)

Landmark Designation and Acknowledgments

Landmark Designation

The American Chemical Society designated the research and professional contributions of Rachel Lloyd, Ph.D., (1839–1900) as a National Historic Chemical Landmark at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln on Oct. 1, 2014. The commemorative plaque reads

Rachel Holloway Lloyd (1839–1900) became the first American woman to earn a doctorate in chemistry in 1887 when she received her degree from the University of Zurich. In the same year, she was hired as a researcher and professor of chemistry by the University of Nebraska, positions she held until her retirement in 1894. Her work on determining the concentration of sucrose in Nebraska-grown sugar beets contributed to the establishment of a commercial sugar industry in the state as early as 1890. Lloyd’s warm personality, cultural refinement, and commitment to scientific research drew young women into the Chemistry Department and earned the university a reputation for nurturing women chemists at a time when they were largely excluded from the field.

Acknowledgments

Adapted for the internet from “Rachel Lloyd, Ph.D., Pioneering Woman in Chemistry,” produced by the National Historic Chemical Landmarks program of the American Chemical Society in 2014.