ACS joins coalition to express concern about visa wage rule

November 9, 2020

Submitted via Regulations.gov

Brian D. Pasternak, Administrator

Office of Foreign Labor Certification

Employment and Training Administration

U.S. Department of Labor

200 Constitution Avenue, NW

Washington DC 20210

Re: DOL Docket No. ETA-2020-0006

Dear Administrator Pasternak,

The undersigned associations, coalitions, and groups come to you jointly to express our concerns about flaws in the Department of Labor’s (hereafter referred to as DOL or Department) Interim Final Rule, published and in effect on October 8, 2020, entitled “Strengthening Wage Protections for the Temporary and Permanent Employment of Certain Aliens in the United States” (hereafter referred to as IFR or DOL High-Skilled Wage rule).

Commenters' Interests

Signatories to this comment have a keen interest in helping to ensure that the U.S. immigration process effectively promotes – with appropriate integrity and security safeguards – the desirability and ability of high-skilled foreign-born professionals to be employed in our country. Many of us are aware that a revised prevailing wage system would better create confidence in the reliability and fairness of U.S. high-skilled immigration. However, we are very concerned about the significant policy shift resulting from the Department’s most recent wage rule. While we have only been given a short 30-day period to analyze the impact of DOL’s IFR, the rule is already in effect and we can conclude that the specific policy approach adopted by DOL neither protects nor fosters a functioning high-skilled immigration system.

The signatories have varying interests and missions. Some act as professional societies for scientists, lawyers, or educators, or human resource managers. Some are trade organizations representing the nation’s business community, or certain industries, or one sector. Others are associations whose members are the nation’s foremost institutions of higher education. Some are advocacy groups. Many of us actively take steps as organizations or through our members to ensure the United States has the capacity to both educate and employ domestic sources of professional talent. Many of us have worked with successive administrations and Congress on issues critical to the global mobility of talent and compliance, functionality, and integrity in the employment-based immigration system of the United States. Despite differences in approach, sector, and membership, each signatory has found it core to our mission as an organization that high-skilled immigration is a key component of the ongoing ability of the United States to obtain and retain the talent necessary for America and American enterprise to continue to innovate and create jobs in the United States.

Member firms and institutions of the undersigned organizations (and where our members are individuals, the employers, clients, and collaborators of our members) are among the nation’s foremost creators of jobs for U.S. workers. They contribute immensely to the nation’s economic strength and global competitiveness. They contribute immensely to the nation’s economic strength and global competitiveness. To maintain that strength and competitiveness, they employ the talents of well-educated and highly skilled professionals who happen to be foreign-born along with the vast preponderance of U.S. workers that make up their workforce. The ability to hire appropriate, eligible individuals in H-1B visa status is an important tool in the ability to bring that workforce together. Established in the 1952 rewrite of the nation’s immigration laws, for over 65 years the H-1 visa classification has existed to allow U.S. employers to hire professionals born outside our country working in an occupation that typically requires the type of knowledge only obtained through completion of a university education. Since 1990, this category has been subject to numerical limits and a Labor Condition Application (LCA), and designated as the H-1B visa – and many of our members expected to utilize the H-1B visa category to continue to employ current professional staff and hire new staff. DOL’s High-Skilled Wage rule directly upsets these reliance interests.

Introduction

It is important to emphasize at the outset that DOL has adopted a dramatic shift in the H-1B and Permanent Employment Certification programs despite stating in its preamble explanation that “[t]he Department does not dispute that allowing firms to access skilled foreign workers can lead to overall increases in innovation and economic activity, which can, in turn, benefit U.S. workers” and that “the Department is certainly in favor of measures that increase economic growth and job creation.” Indeed, there is significant economic literature in peer-reviewed publications extolling the benefits of high-skilled immigration to America and to Americans,[1] that at least to some extent is left unmentioned by the Department – and where mentioned is insufficiently weighed. The IFR’s faulty justification and policy choices create regulatory framework that aggressively obstructs these national benefits in innovation and economic activity.

Given the immediate, direct, and sizable impact of DOL’s prevailing wage changes, we believe it was and remains incumbent upon DOL to seek feedback from the impacted employers in the regulated community ahead of implementation. For the reasons identified in the lawsuits where a Complaint and Motion for Preliminary Injunction were filed to enjoin the High-Skilled Wage rule, we do not believe that DOL has satisfied the legal standard for claiming a good cause exception to the normal requirement to provide advance notice, take comment, and respond to comments under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). But beyond that legal imperative for full notice and comment rulemaking, the Department has promulgated a rule that has significant flaws, including the six described below, which make the rule unworkable.

In December 2018 the Administrative Conference of the United States adopted new recommendations to enhance public engagement in rulemaking, in order to ensure that agencies receive more comprehensive information.[2] This is because agencies benefit when “situated knowledge” is shared as part of rulemaking efforts; in other words, public officials benefit from having access to knowledge that is widely dispersed among stakeholders.[3] “In particular, agencies need information from the industries they regulate, other experts, and citizens with situated knowledge of the field in order to understand the problems they seek to address, the potential regulatory solutions, their attendant costs, and the likelihood of achieving satisfactory compliance.”[4]

At the end of August 2020, the Department adopted new binding regulations on the guidance process, that incorporated recognition of these important principles when DOL announces policy but is not required to engage in notice and comment rulemaking.[5] DOL obligated itself to essential steps to collect and consider public input before finalizing guidance, which it did not afford the regulated community in publishing this IFR. For example, DOL’s regulation governing mere guidance requires the Department to

- allow at least a 30-day comment period before finalizing guidance,

- undergo a cost-benefit analysis review by OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) in full compliance with EO 12866, and

- publicly post a response from DOL “that addresses major concerns raised in timely submitted comments. This response-to-comments should be similar to what typically appears in the preamble to a final rule under the APA” documenting the agency’s response to comments and concerns raised by stakeholders.[6]

DOL’s High-Skilled Wage rule does not abide by any of the above elements, and the following six points demonstrate why public input from the regulated community is crucial to the workable implementation of such a far-reaching rule. As such, the Department should withdraw its High-Skilled Wage rule as published and solicit public comment in the form of a Request for Information (hereafter RFI) and/or an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (hereafter ANPRM), which would inform the Department how best to proceed.

Six Fatal Flaws in DOL's High-Skilled Wage IFR

Prevailing Wages Cannot Be Disconnect from Actual Wages. First, DOL begins the explanation of its IFR by amplifying the point that both the actual and prevailing “wage rates generally should approximate the going wage for workers with similar qualifications and performing the same types of job duties in a given labor market.” The Department observes that it is “a reasonable assumption that, if both the INA’s wage safeguards (actual and prevailing wage obligations) were working properly, the wage rates they produce would at least in many cases be similar.” However, the structure imposed by the IFR does not yield this result—quite the opposite. Adopting a structure that directly contradicts the Department’s self-identified measure of a working prevailing wage structure evidences a significant error in DOL’s IFR. The Department replaced the system in which it believes “prevailing wages are too low” with one that establishes prevailing wages that are unmistakably too high.

Members of the undersigned organizations have found that level 1 wages for jobs offered to their H-1B employees (representing about 14% of all LCAs) increased overnight by an average of 41%-50%, level 2 wages increased on average between 61%-70% (representing 49% of all LCAs), with level 3 and 4 wage rates increasingly haphazardly (between 30%-100%). In addition, thousands of employers report that the new level 1, 2, 3, 4 percentiles of surveyed OES wages codified in DOL’s IFR (identified in the IFR to be at the 45th, 62nd, 78th, and 95th percentiles) are not being implemented as written in new 20 CFR 656.40(b)(2)(i)(A)-(D) and that often the new level 2 prevailing wage (62nd percentile) exceeds the old level 4 prevailing wage (67th percentile), among other anomalies.[7]

To provide examples from occupations outside of the computer-related and engineering jobs typically filled by H-1B professionals, we look at Statisticians (SOC code 15-2041), Accountants (SOC code 13-2011), and Management Analysts (SOC code 13-1111) in New York City. For an employer hiring a Management Analyst at the level 2 skill level, whether a U.S. worker or a worker in H-1B status, the annual salary may have typically been between $90,000 and $110,000 (depending on education and experience level). The prevailing wage was $87,506, but under the IFR is now $150,259, far above the usual wage range. Employers who hired Accountants, whether U.S. workers or workers in H-1B status, at the level 2 skill level, may have typically offered wages between $76,000 and $96,000 (depending on level of education and extent of experience) and now report that DOL’s IFR requires them to pay their H‑1B level 2 Accountants at least $129,854. The level 2 prevailing wage for Accountants in New York City was previously $75,077, while the level 4 prevailing wage for Accountants in New York City was $102,086; thus, under the IFR, the new level 2 wage (supposedly the 62nd percentile of surveyed wages) exceeds the old level 4 (67th percentile of surveyed wages). And some of the overnight prevailing wage increases for employers hiring experienced staff in New York City are just not reflected in the market place for the designated skill level as a general matter, such as IFR-mandated increases for level 3 Statisticians where the prevailing wages moved from $109,824 to $149,822, increasing the required wages by 36%, and for level 3 Management Analysts, which saw a move from a prevailing wage of $110,698 to a new required wage of $207,188, or an overnight increase of approximately 87%. The Department of Labor manufactured a new prevailing wage rate system that is utterly disconnected from the actual wages employers pay similarly situated United States workers.

The DOL IFR also ignores altogether an important evolution over the last decades in professional employment compensation across the United States, whereby many employers add to annual salaries with variable compensation tied to productivity, performance, or other specific goals. The High-Skilled Wage rule will strain the ability of employers to harmonize salaries offered foreign-born professionals and their U.S. counterparts. This strain may also incentivize employers to abandon variable compensation schemes altogether, in order to use available resources in an attempt to meet the new required wages. Attempting to recalibrate resources applied to variable compensation schemes to instead supplement base salary is logical because variable compensation is never considered part of actual wages for purposes of prevailing wage compliance in hiring a foreign-born professional.[8]

The new construct adopted by the Department requires early-career professionals (level 1 and level 2 jobs) employed in H-1B status to be compensated between 90% of the occupational median (45th percentile of surveyed wages, new level 1) and approximately 125% of the occupational median (62nd percentile of surveyed wages, new level 2). Experienced professionals (level 3 and 4 jobs) may not hold H-1B status under DOL’s IFR unless they are compensated far above the occupational median (the 78th percentile of surveyed wages for any professional who is “experienced,” and salary at the 95th percentile for managerial professionals). This new construct does not reflect the market’s reality or current compensation in the U.S. labor market, and, furthermore, might place employers in the position of paying their foreign-born H-1B professionals a markedly higher wage than that paid U.S. workers with similar education, experience, and responsibility.

This disconnect impacts tens of thousands of employers and hundreds of thousands employees. In sharing H‑1B data as part of its transparency efforts,[9] DHS has indicated that something on the order of 49,820 unique employers receive H-1B approvals annually, to cover initial cap-subject and cap-exempt filings as well as amendments and extensions of status, and DHS has estimated that about 583,420 H-1B professionals are currently work-authorized.[10] Most H-1B employers, about 45,000 entities annually, receive under 10 approvals (with about 30,000 employers obtaining one, single H-1B approval); about 4,500 employers receive 10 or more H-1B approvals but less than 100; approximately 300 employers receive more than 100 approvals but not more than 1,000; and about 20 employers received more than 1,000 approvals. The impacts of the IFR will therefore be spread across tens of thousands of employers and hundreds of thousands of employees, forcing sudden increased costs upon businesses. An enduring weakness of DOL’s analysis is that it fails to consider how the new prevailing wage policy will impact the vast majority of employers utilizing the H-1B system Congress created, including employers in academia, research, or not-for-profit activity, those that are start-ups, and those that are small and medium-sized enterprises.

DOL Disregards High Intensity Occupational Activity. Second, DOL relies heavily on the notion that simply because U.S. employers filing the most H‑1B petitions generally pay wages far in excess of the prevailing wage rate, it follows that the pre-IFR prevailing wage structure long in effect identified prevailing wages at levels 1, 2, 3 and 4 that are best characterized as markedly below market rates. What DOL ignores is that the reason these particular U.S. employers pay such high wages is the high intensity of particular work in particular occupations in particular geographies in our country. As DOL well knows, as part of the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) survey the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) identifies for each SOC (Standard Occupational Classification) code in each MSA (Metropolitan Statistical Area) or MD (Metropolitan Division) the number of employed individuals per each 1,000 employed persons in that particular occupation represented by the SOC code. This is a useful proxy for the intensity of activity in that particular occupation in a particular geography. Some of the employers that pay particularly high wages are competing in locations with unusually high intensity in the occupations for which they hire H‑1B professionals.

For example, in the IFR preamble explanation, the Department states that H-1B workers make up 22% of all professionals working in the United States in the Software Application Developer occupation. BLS reports in its raw OES data that across the United States, there are only 26 of the 392 MSAs or MDs where more than 1% of all employed persons in that geographic area work in that one occupation, as Software Application Developers. Omitting double counting where the MSA and MD boundaries overlap, there are less than 20 high intensity geographies for Software Application Developers, where at least 1% of all employed persons work in that single occupation. Given that DOL states that one-fifth of all H-1B workers are in the occupation, that DOL shares in the IFR that about one-fifth of all LCAs are filed by 20 companies, and that many of those companies do business in these high intensity areas and seem likely to hire Software Application Developers by the nature of their business, it is likely that many of the companies need to pay a premium to attract both domestic talent and foreign-born talent – a reality for which the Department failed to account.

All U.S. Locations where Software Application Developers are at least 1% of All Employed Persons in Location | |||

MSA|MD ID # | METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREA OR METROPOLITAN DIVISION | SOC | Per 1,000 |

38900 | Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA | 15-1132 | 10.168 |

35084 | Newark, NJ-PA Metropolitan Division | 15-1132 | 10.186 |

47900 | Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | 15-1132 | 10.223 |

19740 | Denver-Aurora-Lakewood, CO | 15-1132 | 10.919 |

47894 | Metropolitan Division Wash-Arl-Alex, DC-VA-MD-WV | 15-1132 | 11.006 |

16300 | Cedar Rapids, IA | 15-1132 | 11.264 |

39340 | Provo-Orem, UT | 15-1132 | 11.455 |

71650 | Boston-Cambridge-Nashua, MA-NH | 15-1132 | 11.488 |

18140 | Columbus, OH | 15-1132 | 11.591 |

71654 | Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA NECTA Division | 15-1132 | 12.155 |

26620 | Huntsville, AL | 15-1132 | 12.803 |

20500 | Durham-Chapel Hill, NC | 15-1132 | 13.267 |

17820 | Colorado Springs, CO | 15-1132 | 13.732 |

12420 | Austin-Round Rock, TX | 15-1132 | 13.862 |

74804 | Lowell-Billerica-Chelmsford, MA-NH NECTA Division | 15-1132 | 14.301 |

39580 | Raleigh, NC | 15-1132 | 14.462 |

75404 | Nashua, NH-MA NECTA Division | 15-1132 | 14.518 |

41860 | San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward, CA | 15-1132 | 16.064 |

31540 | Madison, WI | 15-1132 | 19.738 |

45940 | Trenton, NJ | 15-1132 | 20.367 |

73104 | Framingham, MA NECTA Division | 15-1132 | 21.708 |

42660 | Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | 15-1132 | 24.536 |

41884 | Metropolitan Division San Fran-Redwood-SoSF, CA | 15-1132 | 24.598 |

14500 | Boulder, CO | 15-1132 | 25.783 |

42644 | Metropolitan Division Seattle-Bellevue-Everett, WA | 15-1132 | 28.644 |

41940 | San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA | 15-1132 | 39.689 |

Source: BLS from OES data

The 30-day comment period does not allow sufficient time for the necessary analysis to validate that the LCAs with wages in excess of prevailing wages are primarily for such high-intensity jobs and locations. Of course, DOL has access to the data to analyze this issue and could have taken the time to conduct the necessary research before devising its policy solution to revise the prevailing wage rates. It appears that DOL did not consider this reality or evaluate it.

DOL Improperly Relies on Median Wages and Presumed Wage Suppression. Third, with respect to economists who have studied high-skilled immigration in peer-reviewed journals, the Department fails to cite and consider economists’ data-based studies specifically addressing the wage impacts to U.S. workers of the wages paid to H-1B workers. Instead, DOL primarily relies on policy analysts that are aware that “(c)onceptually, the market wage is the wage a U.S. worker would command for a position in a specific occupation and region,” but nevertheless, for H-1B workers, they “believe that the most reasonable and closest proxy for a market wage is the median wage for an occupation in a local area,” without evidence for why the median could be the most reasonable and closest proxy.[11]

DOL adopted this “belief” as its own, resetting the level 1 wage as 90% of the occupational median wage in the job location and resetting the level 2, 3, and 4 required wage rates in excess of the occupational median. Yet, by way of example, no employer in any sector in any geography in our country sets compensation for those completing graduate or professional degrees with little professional experience (these are typically level 2 professionals, that amount to approximately 49% of all H-1B Labor Condition Applications), above the median wage for all professionals in the occupation in the job location.

DOL states multiple times throughout the preamble explanation that it was compelled to adopt its new prevailing wage approach because H-1B workers suppress wages for U.S. workers, yet that is not what economists have found from data-based analysis.

One seminal economic analysis found that between 1990 and 2010, a 1 percentage point increase in the “foreign STEM share of a city’s total employment”—“made possible by the H-1B visa program”—increased the wage growth of U.S.-born college-educated labor by 7–8 percentage points and the wage growth of non-college-educated U.S.-born workers by 3–4 percentage points.[12] Moreover, even curbing H-1B inflows directly, regardless of prevailing wages paid to H-1B visa holders, will not increase wages paid to domestic workers as evidenced by an economic study that modeled the “complete elimination” of the H-1B visa program and found “essentially zero” change to wages for high-skilled Americans in year one and a slight reduction in wages for high-skilled Americans by year three.[13]

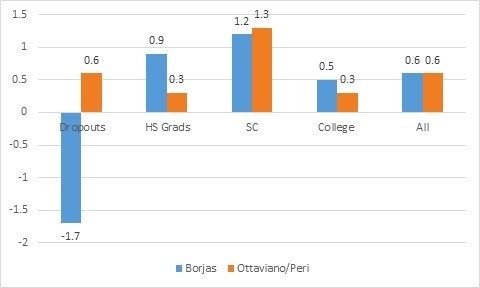

Perhaps more definitively, when the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine completed a literature review in 2016 on the economic and fiscal impacts of immigration in the United States there was a broad consensus with respect to high-skilled immigration that any impacts on U.S. wages by high-skilled, college-educated foreign-born professionals are close to negligible.[14] While DOL repeatedly cites to the economist George Borjas and his study of low-skilled immigrant labor as being instructive to the wage impacts of immigration on the general labor market, the Department fails to recognize that with respect to high-skilled immigration Borjas was a significant contributor to the 2016 National Academies report and did not find a negative wage impact from high-skilled immigration. In the National Academies study, Borjas reported that wage impacts from immigrants on the U.S.-born college-educated workforce is minor (an increase for U.S. professionals of one-half of one percent in wage rates as a result of high-skilled immigration), as shown on the following table:

Percentage Increase (or Decrease) of Native-Born American Wages Resulting from Immigration

Source: George Borjas, Immigration Economics (2014) at p. 120; and G. Ottaviano and G. Peri

Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages, Journal of the European Economic Association

(October 2011) at Table 6.

Note: Table and a large part of the National Academies 2016 results on wage impacts from immigrants reflect the work of George Borjas (who looked at 1990–2010 data) and of Gianmarco Ottaviano with Giovanni Peri (who looked at 1990–2006 data). Table compares wage impacts of immigration on high school dropouts, high school graduates, individuals with some college (SC), and college graduates – and then an average of all education groups.

Most recently, in reviewing the DOL IFR, the American Action Forum’s economic analysis explained, “The central argument for raising the required wage is that the economic situation of American workers has changed so drastically that it has become necessary to fast-track changes to wages in order to protect American workers. The reality is that the changes made to wage levels do little to help workers and could put much-needed economic recovery at risk.”[15]

Early-Career Master’s or Bachelor’s Graduates Cannot be Excluded. Fourth, the Department’s IFR does not match its preamble explanation that it is not trying to price the hire of early-career, foreign-born Master’s professionals out of the U.S. labor market by increasing the minimum required wage to the average of the fifth decile of surveyed wages (the 45th percentile of OES surveyed wages).[16] As directly permissible under the governing INA,[17] 63% of LCAs are filed for early-career professionals (49% at level 2, 14% at level 1) many of which are international students earning degrees at U.S. colleges and universities, especially at the graduate level. This is all consistent with the fact that nothing in the statute contemplates or suggests that DOL could ever take a position to disfavor young professionals from securing H-1B status by working at a skill level 1 or 2 in a specialty occupation.

Moreover, despite DOL’s protestations to the contrary,[18] the High-Skilled Wage rule also strongly disfavors hiring foreign-born professionals who lack graduate training. DOL ignores its own data that establishes that about an equal number of individuals in H-1B status with advanced degrees and Bachelor’s degrees are sponsored for green card status through Permanent Employment Certification applications.[19] And then the Department seemingly relies, improperly, on a court case about lesser skilled H-2B temporary workers for authority that the Department may presume that H-1B workers being sponsored for Employment-Based Third Preference have readily available, Bachelor’s level skills.[20] It is a hollow assurance from DOL that a Bachelor’s degree continues to be a permissible minimum requirement for an offered job in a qualifying H‑1B specialty occupation when in effect the lowest (minimum) prevailing wage requirements are specifically set in an imperfect attempt to capture the high end of wages paid professionals with graduate degrees.

DOL Failed to Address Reliance Interests. Fifth, the Department ignores the reliance interests of tens of thousands of employers[21] who may be unable to continue to employ their current H‑1B professionals on staff. DOL’s preamble explanation makes clear that it established its new High-Skilled Wage rule for the nation’s employers without taking any affirmative steps to assess or understand hiring practices or implications to a variety of occupations, geographies, sectors, and employers. These varied interests, including those of non-profits, research institutions, rural hospitals and health clinics, universities and colleges, start-ups, and small businesses, are represented by many of the undersigned organizations. It is not a partisan analysis or partisan concerns that lead the undersigned to conclude that the Department failed to consider reliance interests. As the American Action Forum research concluded, “Changes of this magnitude to the wage requirements, especially for entry-level workers, will adversely affect firms, such as nonprofits and startups, that have limited financial resources but rely on skills that H-1B workers bring. By making it more expensive to hire workers, the rule change would further discourage foreign-born students from attending American colleges and universities, despite the fact that they support the departments and programs that teach high-demand skills to both native and foreign-born students.”[22]

The mandated wage increases for H-1B professionals also have a multiplier effect, injecting damaging, new uncertainty into the capacity and productivity of the member firms and institutions of the undersigned associations at this moment in our nation’s history when our economic life already includes many unexpected challenges from the COVID-19 global pandemic. This is because the Department’s rule will artificially create both churn and more broadly turnover. Economists define “churn” as hiring for replacement, which means that a prior worker, being replaced, left voluntarily or was terminated. While turnover includes churn, businesses also experience turnover because employers grow and shrink.

As a result of the DOL IFR, some employees simply will not and cannot qualify to continue employment because the employer has insufficient resources, creating the possibility of costly churn. For highly-skilled professionals, it is typical that recruitment, hiring, and replacement costs, on average, approach about 30% of the salary level for a professional worker. Thus, DOL first creates uncertainty about the ability to continue the employment of hundreds of thousands of current professional staff and then vastly understates the cost of replacing H‑1B workers.

But here DOL’s wage increases also have a broader, turnover-causing impact. For equal employment and other reasons, employers that are required to increase wages for high-skilled, foreign-born professionals would typically increase wages across the board for all individuals in certain occupational categories. Because employers cannot absorb the attendant costs on the scale envisioned by DOL, employers will instead need to reduce hiring or lay off parts of their workforce because they cannot absorb these costs. Thus, “[u]nfortunately, the new rule is likely to harm U.S. businesses – particularly startups and nonprofits – and hinder the economic recovery.”[23]

DOL likewise understates or ignores altogether the reliance interests of the H-1B professionals employed in the country now.[24] Some of the undersigned organizations have informally polled their members at this early juncture in the implementation of the new High-Skilled Wage rule and learned that many have made initial estimates that 65%-70% of all individuals being sponsored for green card status through a Permanent Employment Certification may be unable to continue in the process. These individuals, and their families, often have purchased a home, developed permanent ties to the United States, or made a decision to have children here, counting on obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident status.

While it is not possible within the 30-day comment period afforded to calculate the dollar value of these reliance interests, they were not discussed or addressed with specificity by the Department. This is the very cost-benefit analysis usually reviewed by and perfected after follow-up inquiries from OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) that never occurred in the instant rulemaking. OIRA review was inexplicably waived in this rulemaking as DOL rushed to publish and implement dramatic changes to the high-skilled prevailing wage system. We suggest that DOL restart the rulemaking process concerning high-skilled wages by publishing a RFI and/or an ANPRM and ask the public to calculate potential impacts of various alternative options identified by the Department, so DOL has fulsome information to assess and thereafter decide how to proceed.

DOL Avoided Careful Consideration of Alternatives. Lastly, there are a number of alternatives that DOL could have considered and did not, in order to improve the prevailing wage system for high-skilled immigration. While the OES survey is likely the best data source available, the OES survey neither collects specific salary figures – as opposed to pay band information – or connects pay bands to the education, experience, or responsibility of employees as required by the INA’s language.[25] One solution to achieving increased accuracy of the wage rates calculated by Office of Foreign Labor Certification for immigration purposes based on the OES survey is to combine the far-reaching data collection of the OES survey with certain data from private, independently published compensation surveys.

While authoritative independent surveys are not available for all occupations in all localities, they are available for many high-skilled occupations for which H-1B petitions and Permanent Employment Certification applications are filed and uniformly do collect information on the education and experience of surveyed employees, as well as specifically salary figures (instead of pay bands). Currently, high-skilled immigrant professionals are primarily in the science and engineering occupations. The Department of Homeland Security reports that 76% of all H-1B visa petition approvals are in computer-related, mathematical, and engineering occupations and, correspondingly, the Department of Labor reports that 68% of Permanent Employment Certifications approved to sponsor new green card holders are in the same computer, mathematical, and engineering occupations, with most (also 68%) such labor certifications filed on behalf of H-1B visa holders. It is in these very occupations that private sector compensation surveys often provide coverage. There are also are extensive compensation surveys available in many healthcare occupations, another group of jobs for which there are commonly H-1B petitions filed. DOL could establish a system where the Bureau of Labor Statistics would utilize certain fields of data available from such surveys. BLS economists and statisticians could then layer this additional information over the OES data. This should provide all parties involved with more accurate prevailing wage determinations that rely on real world conditions.

Conclusion

In October 1991, the Department stated its obligations with respect to implementing the H-1B Labor Condition Application (LCA), when it first codified regulations governing the then-new LCA process: “The Department believes that Congress, in enacting the Act [the Immigration Act of 1990, that created the LCA obligation and the requirement for employers to pay the greater of actual or prevailing wages], intended to provide greater protection than under prior law for U.S. and foreign workers without interfering with an employer’s ability to obtain the H-1B workers it needs on a timely basis.”[26] The IFR published October 2020 does not protect U.S. workers and directly interferes with an employer’s ability to obtain the H-1B workers it needs.

We value the opportunity to participate in the rulemaking and policy implementation process. The issues set out above are only some among what we consider to be most important shortcomings in DOL’s High-Wage rule, but they are the central ones for the undersigned organizations.

For the six reasons set out above, we urge DOL to take steps to rescind the IFR. And, should a court strike down the IFR, we ask that DOL start anew with a RFI and/or an ANPRM to first gather input from the regulated community on this important topic.[27] Many of the undersigned organizations stand ready to assist the Department in working toward a new prevailing wage system for U.S. high-skilled immigration.

Respectfully submitted,

American Chemical Society |

International Medical Graduate Taskforce

Internet Association

Materials Research Society

NAFSA: Assosciation of International Educators

National Immigration Forum

Semiconduct Industry Association (SIA)

Society for Human Resource Management

TechNet

U.S. Chamber of Commerce

Unshackled Ventures

Worldwide ERC®

[1] A sampling of the peer-reviewed literature that the Department failed to evaluate includes: A Journal of Economic Perspectives study on Global Talent Flows (Fall 2016) found very little displacement of U.S.-born innovators and high-skilled professionals by high-skilled immigrants, while also identifying significant boosts to innovation and productivity by such immigrants. In a Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics (2015), economists found that foreign-born workers boost productivity of native-born Americans at the local level. In the Labour Economics journal (December 2019), economists found that the foreign-born share of STEM professionals in the United States increased from about 16% to 24% over the period 2000 to 2015 creating an estimated benefit of $103 billion for American workers almost all “attributed to the generation of ideas associated with high-skilled STEM immigration which promotes the development of new technologies that increase the productivity and wages of U.S.-born workers.” A July 2018 economic study on High-Skill Immigration, Innovation, and Creative Destruction concluded from firm-level analysis that H‑1B visa petitions are associated with higher rates of product reallocation for American firms (entry of new products and exit of outdated products). See also, e.g., Alex Nowrasteh, Don't Ban H-1B Workers: They Are Worth Their Weight in Innovation (Cato Institute, May 14, 2020), for a summary of the peer-reviewed economic literature about the value of H-1B professionals and high-skilled foreign-born workers in the United States economy that DOL did not identify or consider in developing or explaining its approach to the High-Skilled Wage rule.

[2] 84 Fed. Reg. 2139, 2146-2148 (February 6, 2019), Administrative Conference Recommendation 2018-7, Public Engagement in Rulemaking (adopted December 14, 2018).

[3] M. Sant’Ambrogio and G. Staszewski, Michigan State University, Public Engagement with Agency Rulemaking (Administrative Conference of the United States, November 19, 2018) at p. 3.

[4] Id. at p. 10.

[5] 85 Fed. Reg. 53163 (August 28, 2020), Promoting Regulatory Openness Through Good Guidance.

[6] Id. at 53169.

[7] For a summary of anomalies in the High-Skilled Wage rule see, e.g., David Bier, DOL's H-1B Wage Rule Massively Understates Wage Increases by up to 26 Percent (Cato Institute, October 9, 2020), Stuart Anderson, An Analysis of the DOL H-1B Rule (National Foundation for American Policy, October 2020), and Stuart Anderson, Flaw in DOL Rule Sets H-1B Salaries at $208,000 a Year (Forbes, November 2, 2020). Because (pursuant to Section 212(p)(4) of the INA as codified by DOL at new 20 CFR 656.40(b)(i)(B)-(C)) the level 2 and 3 wages cannot be calculated without first calculating a level 1 and 4 wage for each occupation in each job location, where the 10th decile average (level 4) is unavailable from the OES data, the implementation of the IFR collapses. The IFR does not appear administrable, in that prevailing wages often do not match the percentiles for each wage level detailed in the IFR and in many situations for highly compensated individuals a “default wage” of $208,000 per year is created.

[8] See 20 CFR 655.731(c)(2)(v), establishing that satisfaction of the wage obligations for an H-1B employer excludes any bonuses or variable compensation that is not assured.

[9] H-1B Employer Data Hub files provided by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the component of DHS that adjudicates H-1B petitions.

[10] H-1B Authorized-To-Work Population Estimate, was published in June 2020 by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

[11] Daniel Costa and Ron Hira, H-1B Visas and Prevailing Wage Levels (Economic Policy Institute, May 4, 2020) at p. 5.

[12] Giovanni Peri, Kevin Shih, & Chad Sparber, STEM Workers, H-1B Visas, and Productivity in US Cities, 33 J. Labor Econ. S225, S252 (July 2015).

[13] Michael E. Waugh, Firm Dynamics and Immigration: The Case of High-Skilled Immigration, Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research (Working Paper No. 23387, 2017) at 14, 27–29. Similarly, when polled in 2017, not a single member of the University of Chicago’s Initiative on Global Markets Economic Experts Panel—which includes over 40 leading economists from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, MIT, Stanford, and Berkeley—agreed with the following proposition: “If the U.S. significantly lowers the number of H-1B visas now, employment for American workers will rise materially over the next four years.” High-Skilled Immigrant Visas (Question B on H-1B Reduction), University of Chicago Booth School of Business (Feb. 14, 2017).

[14] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration

(September 2016, published as free download January 2017).

[15] Isabel Soto and Tom Lee, Assessing the Department of Labor's Rule Raising Wage Requirements for H-1B Workers (American Action Forum, November 3, 2020) at p. 2.

[16] Of the 20 pages in the Federal Register (p. 63876-63896) covering DOL’s “Reasons for Adjusting the Prevailing Wages,” 10 pages (p. 63887-63896) are devoted at least in part to an attempt by DOL to explain its dependence on Master’s level credentials as the standard for the new level 1 prevailing wages while suggesting it is not establishing possession of a graduate degree as a new minimum requirement.

[17] INA Section 214(i)(1). See, e.g., Matter of B-C Inc. (decided January 25, 2018) confirming that the skill level required for the job duties (skill level 1, 2, 3, or 4) does not control whether it is in a qualifying specialty occupation.

[18] See, e.g., “The Department notes again by way of clarification that it is not suggesting that possession of a master’s degree is required to work in a specialty occupation.” (footnote 168 in the IFR preamble at p 63890).

[19] Permanent Labor Certification Data (September 30, 2019) shows that 43.4% of all Permanent Employment Certifications are approved for advanced degree holders and 41.1% for Bachelor’s degree holders.

[20] DOL cites to an H-2B case to not only discuss that it is core to the INA for the Department to balance the interest in certain industries for foreign-born workers with the protection of U.S. labor, but also to raise the idea that is reasonable to presume Bachelor’s-level U.S. workers are likely readily available (footnote 201 in the IFR preamble at p. 63896).

[21] As discussed supra, DHS information on the transparency pages of the USCIS website state that around 49,820 individual employers each year obtain H-1B approvals.

[22] Isabel Soto and Tom Lee, Assessing the Department of Labor's Rule Raising Wage Requirements for H-1B Workers (American Action Forum, November 3, 2020) at p. 1. Douglas Holtz-Eakin, PhD, George W. Bush’s first Chief Economist for the Council of Economic Advisers and later his Director of the Congressional Budget Office, is President of the American Action Forum.

[23] Id. at p. 6.

[24] As discussed supra, DHS information on the transparency pages of the USCIS website state that around 583,420 individual employees are presently work-authorized in H-1B status.

[25] INA Section 212(p)(4).

[26] 56 Fed. Reg. 54720 at 54271 (October 22, 1991).

[27] When DOL first codified the new LCA requirements that had been created by the Immigration Act of 1990, including prevailing wage requirements, DOL made sure to secure public comment, multiple times, to which the Department provided a fulsome response. DOL published an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rule Making (ANPRM) to which public comment was requested (56 Fed. Reg. 11705, March 20, 1991), and only thereafter published a Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM), considering comments already received from the regulated community (56 Fed. Reg. 37175, August 5, 1991). DOL followed with an Interim Final Rule where it explained the DOL’s consideration of both the comments previously provided to both the ANPRM and NPRM and allowed further comment (56 Fed. Reg. 54720, October 22, 1991).